The Class 800 debacle

It was Winston Churchill who said “Never let a good crisis go to waste”.

It’s in that spirit that I’m writing this post.

If we don’t take advantage of the Class 800 debacle to look closely at how things could have been better for customers, we’ve missed a golden opportunity.

The danger, of course, is that it may be a bit raw for all those people who’ve already had a week of hard work, sleepless nights and little reward to show for it.

So for all those people who’ve not had nearly enough sleep in the last week, thank you for all you’ve done.

This post is about systems, processes and culture: not about you.

Ocado

On the morning of 5th February 2019, the managers of Ocado were disconcerted to find that one of their four UK distribution centres now looked like this:

Ocado distribution centre in Andover on the morning of 5th February 2019

The building, the machinery and all the stock in the Andover distribution depot were destroyed.

Within days, Ocado was running a normal service. They achieved this by reneging on a deal to provide Morrisons with distribution capacity in its Erith store in South East London and completely changing its rosters and schedules to add new routes from its remaining depots. Customers who had cancelled bookings from Andover were able to rebook online automatically and within hours of the fire starting it was no longer possible to book slots that didn’t exist. Most customers wouldn’t have noticed anything had happened at all.

It’s not ideal to have to rebook an online delivery that didn’t show up, but, let’s face it, this isn’t an appalling customer experience given what had just happened (the Twitter exchange below occurred a few hours after the fire started):

Not a bad response considering that one of just four distribution depots remaining a smouldering wreck, and £5m worth of stock had just gone up in smoke.

Ocado, in a dogfight with the other online supermarkets, simply did not have the option of the railway approach and simply telling its customers in Southern and Western England to go away for a week or so.

KFC:

Now, the Ocado situation isn’t a perfect parallel for the GWR situation. The depot was obviously going to be out of use for months, so they might as well get on with putting contingencies in place. OK, so it’s pretty impressive how quickly they got a normal service restored, but what about a situation which is known to be temporary and of indeterminate length?

A closer parallel to the Class 800 debacle was KFC’s chicken crisis of 2018.

Back in February 2018, KFC had tried to cut costs by transferring their chicken distribution contract from specialist catering distributors BidVest to DHL who, it turned out, knew next to nothing about distributing perishable goods.

Within days, virtually every KFC branch in the UK had run out of chicken. As with GWR, they had no idea how long the crisis would last and - as with GWR - it turned out to be much longer than initially hoped. It took nearly a week to get every store open again.

While the failings of their contractor meant they couldn’t deliver a service, they did what they could do and re-engineered their website so as to provide a store-finder on the front page that provided a live list of which stores were open:

Given that no-one needs KFC and virtually every KFC has a Chicken Cottage or another KFC-clone round the corner, you could ask why on earth KFC bothered. All they needed to do was put a message up saying ‘we’re shut’ and all would be well.

But, of course, the fact that the fried chicken market is so hyper-competitive is precisely why KFC did need to do everything they could.

Silverlink metro

This next one is slightly smaller scale…

We’re going back to 2004 and I’m a duty station manager at Euston. One day the 1627 stopping train to Watford is cancelled. I get on the phone to Control and agree a special stop order for the 1624 train at Queen’s Park, so that passengers can change onto the Bakerloo line, which serves many of the same stations. Unfortunately, I’m so busy phoning control, filling out the special stop order three times on its special pad, finding a dispatcher to give a copy to the driver and another to the guard, that I fail to tell the announcer. I realise my mistake at 1622, which means that the entire trainload of passengers pour round the corner onto the platform just as the 1624 pulls out of the station.

I do the only thing I can think of at the time: put my namebadge on, go onto the platform and shout “I’m so, so sorry. That was entirely my fault.” At which point, of course, everyone forgives me and they all wait for the next train.

This whole thing may have lasted less than 30 minutes but it was an unforgettable learning experience. The way the rail industry works means you sometimes work incredibly hard when something goes wrong and you can still fail to deliver a decent customer outcome. (especially when the operational task is so pressing that informing the customer gets pushed to the back of your mind)

In such circumstances, it’s tempting to judge the outcome by the intensity of your own work.

“I worked really hard so the outcome must have been good”.

But it’s a trick.

A bad outcome is still a bad outcome, even if you sweated blood for it.

Which brings us to the Hitachi crisis…

GWR

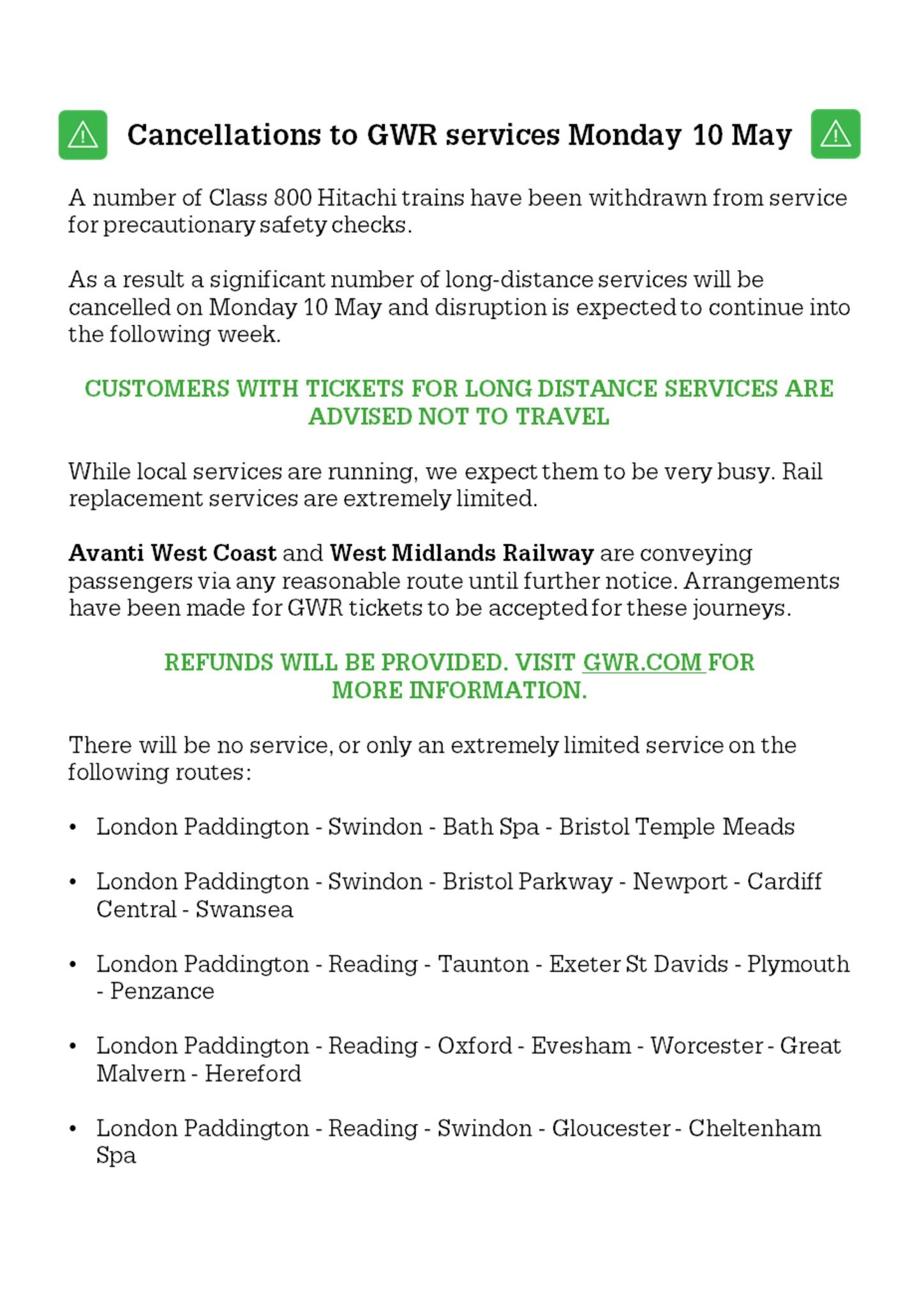

48 hours after their distribution centre went up in smoke, Ocado were already delivering a completely normal service. KFC were still completely stymied but had comprehensive online information. Here is the situation on GWR after 48 hours:

1) The online information consists of a single webpage with virtually no information, simply encouraging me not to travel at all

2) No alternative rail services are being publicised and almost none have been run.

3) The adjacent South Western Railway franchise, which has traction and route knowledge to many key GWR destinations such as Bristol and Exeter, is running its timetabled service which, currently, includes no direct trains to London from either Exeter or Bristol

4) No rail replacement coaches have been provided despite this crisis occurring during a period when coach tours are banned and virtually every coach company in Britain has a yard full of coaches and is desperate for work

5) Online timetables still show the normal timetable for tomorrow and every other day this week, despite the certainty these won’t be running. Websites like Trainline (and GWR’s own website) are selling reservations for trains that are certain not to run, with Advance fares allocated to them

So let’s now imagine I’m someone in Falmouth who is attending a funeral in Braintree on Tuesday 11th May, and it’s now 10AM on Monday 10th May. I have seats booked on GWR from Falmouth (leaving at 0711) to Paddington and onwards to Braintree via Greater Anglia, arriving into Braintree at 1450 for a 1600 start.

I’ve heard on the radio that there is a problem with the trains.

Here are some questions I might have:

Will my train run tomorrow?

If not, will there be an alternative train?

If not, how will I get to the funeral?

Should I start today and stay overnight?

(Assuming I know enough about the railway to know that another train company runs from Exeter) Should I drive to Exeter and use the train from there tomorrow?

If I do, will I be able to use the same ticket?

If a train is running, will it be safe (given what I heard on the radio)

What exactly is going on? What’s the actual problem?

If there’s not total clarity right now, at what time should I check back?

So now I check the Trainline website and my train is still listed as running. Good: I’m feeling pretty reassured. But I also go onto the GWR website to check. Scroll back up this page to see the information currently available.

As you can see, it doesn’t help me answer a single question that I have. And it certainly doesn’t help me find a way of getting to the funeral.

So despite everyone’s incredibly hard work and lack of sleep, customer outcomes are woeful.

WHAT HAPPENED?

Well, it certainly wasn’t that people didn’t work hard. I know from friends at GWR and from Railway Twitter just how hard everyone worked.

Instead, I put it down to five things:

1) Systems

Despite £22bn of income every year, the rail industry has not been incentivised to invest in flexible, dynamic timetable and scheduling systems. Indeed, it sometimes seems like it’s not really thought of as a gap.

In a fantasy world, GWR could have done exactly what Ocado did and simply redrawn all its rosters immediately and upload fresh information to its systems.

After all, like Ocado, FirstGroup had sufficient resource to move everyone to where they needed to be. It just wasn’t in the right place.

In the fantasy world, both GWR and SWR would have thinned out services elsewhere in order to deploy resources to where they were now needed. In that world, SWR would have run trains from Exeter and Bristol direct to London. They have both drivers and traction capable of doing so. But, of course, they didn’t.

Indeed, probably the biggest symbol of the systems and process failings of the rail industry in the last week has been SWR running a timetable that saw not a single direct train on either of those routes for the entire week.

2) Flexibility

I’m guessing that even had the systems been in place to enable GWR and SWR to draw up a completely new timetable overnight, the workforce flexibility simply wouldn’t have been there. The day of the Andover fire, Ocado drivers from Erith suddenly found themselves delivering to Southampton. I doubt that it would have been so easy to redeploy drivers, guards and maintenance staff. I don’t mean from a route knowledge point of view: just an acceptance that, in a crisis, the booked roster would need to be torn up (had the systems been in place to create the new ones).

3) “Trains not people”

Like all train companies at the moment, GWR is paid to run trains, not to get people to their destinations.

The importance of precisely who the customer is becomes so visible in a crisis like this.

Because GWR thinks in terms of trains, not people (and is paid to do so), the automatic corporate response is to publicise a list of train routes that would not be running.

Even after an entire week, the only information available to customers was a list of alternative services based around railway geography. Remember, most passengers don’t know railway geography. If all you know is that you live in Bath and want to be in London, what do you make of information like this:

Were GWR paid by customers and not the Government (and culturally driven to think in people flows not railway routes), perhaps they would have created a web service that gave alternative routings - based around customer journeys.

For example, if you searched for Cardiff to London you might get a piece of text that says something like this:

There are three main options. For all of these options, you can use any Cardiff to London ticket valid today, regardless of what train it was originally booked on:

1) CrossCountry train from Cardiff to Birmingham New Street, then Avanti West Coast train from Birmingham to London Euston. Trains depart at 45 minutes past each hour with a total journey time of 4 hours and 15 minutes.

2) GWR train from Cardiff to Salisbury, then South Western Railway train from Salisbury to London Waterloo. Trains depart at 30 minutes past each hour with a total journey time of 4 hours.

3) Local train to Newport, then GWR train to Swindon or Reading and then a GWR train to London Paddington. These trains do not depart at the same minutes past each hour and the journey time varies in different hours. Typically this option will take around 2 hours 30 minutes to 3 hours but involves an extra change. To see the precise times each hour, use the journey planner to search for Cardiff to London with a via location of Swindon.

This is people-focused information, not train-focused information - but it is not what the system incentivises operators to provide.

4) Rules.

I’m fascinated to know why there were no (meaningful) rail replacement coaches put in place. It can’t be lack of coach supply (often a big issue with emergency rail replacement) as coach tourism is currently illegal. There literally has never before been more underutilized road capacity. Is it because GWR couldn’t get hold of the right person at DfT to sign off on expenditure, and that’s what’s now required? Is it because there’s too small a pool of wheelchair accessible coaches and GWR didn’t get the appropriate authorisation under the derogation enabling standard coaches to be used until September 2021? My guess is that’s a combination of all of the latter. My guess is that it was just too difficult. A commercial organisation would have just got on with it as the thought of leaving customers without travel would have been unacceptable. Remember, Ocado reneged on a contract to get its customers the goods they’d ordered.

All this stuff matters, because how customers are treated matters. If the railway is going to fulfil its potential, it can’t have a default that, when things go wrong, customers are simply told to go away.

There are obvious operational constraints that Ocado doesn’t have to deal with. Train drivers need route and traction knowledge; and Ocado drivers do not. Trains need to be timetabled along tracks, whereas Ocado vans only need to be timed at calling points (depots and customers’ homes).

But my contention is that if systems, culture and rules had been different; more customers could have made journeys last week. That matters for the future of the railway, and it matters for the people who missed funerals, job interviews and holidays as a result of being told not to travel.

“Why aren’t we doing it now?”

When I joined National Express coaches in 2004, I arrived in the aftermath of a management conference that went down in NX legend.

This was, you’ll remember, before Megabus or Flixbus; when NX had a monopoly on long-distance coach travel.

Denis Wormwell was on the conference stage delivering his keynote speech when he was interrupted by an aide, who passed him a note. Denis read it, looked worried and said, “Listen, everyone, I’ve just been told that Virgin have announced the launch of Virgin Coach. It’s a direct competitor to National Express.” He then shared the bit more information that was known, including the launch date of the Virgin network. He concluded by saying “This is a serious threat to our business. I’m scrapping the planned agenda for the rest of the conference and let’s just work out what we’re going to do to respond.”

The room was filled with people coming up with ideas for how NX could improve. At the end of the conference, Denis revealed that the Virgin Coach launch was a hoax. But, as he pointed out, “If we should be doing all these things to respond to Virgin, shouldn’t we be doing them anyway?”

GWR is a Government contractor that doesn’t feel the heat (in the way Ocado or KFC do) if it loses customers, so genuinely feels it has no alternative but to tell them to go away in a crisis.

Things could be different if we made them different

The fantasy world I describe in this post doesn’t exist.

My worry is that we forget that it could exist and instead judge outcomes by the degree of effort put in.

Like me on the platform at Euston, so much effort has gone into fixing the operational crisis in a railway environment in which everything is difficult and requires disproportionate effort. Understandably, the people who’ve put in all that effort may not want to reflect on how much better things could have been in different circumstances. But if we don’t think about it now, when will we?

I can imagine what it’s been like to work at GWR during the last week as I was a director of Chiltern Railways when the Harbury landslide severed our railway without warning. I know from my own experience that a lot of people have worked very hard this week and got far too little sleep, and they deserve all that effort to result in better outcomes.

I have written on these pages before of the value of competition on long-distance railway routes.

In that world, long-distance services would be run by commercially focused, competitive operators who’d be holding Network Rail’s feet to the fire on their ability to make changes at 24 hours notice while investing in their own systems, processes and culture to make it possible.

Instead, it looks almost certain that the Williams Review is going to create a ‘Guiding Mind’. The acid test for that Guiding Mind will be when a similar crisis occurs in, say, five years time. Will the customer response be to tell the customers to go away, or will it be like Ocado’s in which most customers barely notice?