Train fares don’t make sense. Now’s the time to fix them

I went for a country walk in Plumpton yesterday.

I hope you did too.

Why? Well, normally the flexible train fare from London for a family of four is £45 for a day return, even with a Family Railcard. Completely unaffordable for a few hours in the countryside.

But last weekend, it was just £28.

And, no, this is not a promotion by Plumpton Parish Council to encourage visitors; it is simply a symptom of the crazy way train fares work.

How do train fares work?

British train fares are the dish created by the following recipe:

1) Start with the fares that British Rail charged in 1993.

2) Increase them annually by RPI+1/RPI-1/RPI depending on political tastes at the time.

3) Enable train operators to add additional non-regulated fares over the top: generally used to provide discounts for travel at quieter times or to compete with other operators

4) Where all these crash into each other, Trainline automatically combine tickets for local legs if cheaper than a through ticket

There are, of course, further complexities (for example, some places have higher or lower fares as a result of ‘flex’, when train companies used to be able to hit the RPI average even if individual increases were higher or lower) but we won’t go into these right now.

As a result, fares tend to be lower when British Rail fares were lower in 1993 or because competition has pushed fares down. Even competition that no longer exists tends to be baked into the system as a result of behavioural undertakings made to the Competition Commission when competition is removed.

It is the latter factor that explains why I went to Plumpton yesterday.

Normally the fare to Plumpton is set by Southern and is typical for the distance in the South East of England. But yesterday, engineering works meant the Plumpton trains were diverted from London Victoria to London Bridge.

Because they called at Wivelsfield on the way, that means that Trainline automatically sells you a ticket to Plumpton by splitting the journey at Wivelsfield. London Bridge to Wivelsfield is just £12.50 return because it is on the Thameslink route; and back in the late 1990s when Thameslink was run using rather grimy trains competing with Southern’s brand new shiny ones, Thameslink slashed prices to grow market share.

Thameslink in the early noughties: shabby, grimy trains - and low fares

Then the DfT combined Southern and Thameslink into one franchise and it was agreed that the lower Thameslink fares would be maintained even with the competition removed.

So my discounted fare to Plumpton is a result of historic price competition introduced for a reason that no longer applies, engineering work and unintentional split ticketing.

(BTW - an interesting point is that I only went because it’s half price. The normal fare is unaffordable: who’s going to spend £50 on a day trip to Sussex - the petrol for a return from London to Plumpton would cost about £15. Maybe the accidental rate is right for the weekend leisure market, and the official fare is wrong?)

Now this example is extreme, but it’s not unusual.

12 car trains by accident

Indeed, if I wrote a book on train fares, I might call it “How Britain spent £6 billion by accident.”

The £6bn in question is the Thameslink Programme (£6bn), and I’m being totally tongue-in-cheek. For total clarity, I fully support the Thameslink upgrade, it was totally necesssary and am very glad it happened. But it’s still fascinating to consider why quite so much capacity was required.

Here’s a table showing growth in station entries/exits between privatisation and the Thameslink programme being approved in 2008. Those highlighted in green saw meaningful fare competition between rival operators.

In the first decade of privatisation, total entries/exits from stations across the country increased by 55%. But most stations saw growth below this level: the average was pushed up by outliers; including Cambridge and Brighton.

Unlike Winchester, Bournemouth or Guildford, both of these places saw meaningful price competition between two rival operators to two different London terminals.

(Reading technically had competition as well, but Thames Trains and First Great Western tended not to compete on price between Reading and London, presumably because of the customer confusion that would result given their trains operated on the same route).

No-one sat down and decided that Brighton and Cambridge should have lower fares (or, indeed, should benefit from price competition) - it just happened as a result of the franchise map. It’s impossible to prove the counterfactual, but it seems likely that Brighton and Cambridge saw exceptional growth in part because prices were held down.

Some people might say that the growth of these places was nothing to do with fares and just because they were nicer places to live, so more people moved to them. And it’s possible but, equally, Winchester regularly tops magazine polls for the best place in Britain to live, while Oxford’s growth in this period was almost twenty percentage points behind Cambridge’s.

It is likely that a significant part of the reason why capacity became so constrained on these services (directly feeding the spec for the Thameslink programme with its higher frequency 12 car trains) is because price competition drove down fares. The Thameslink annual season ticket from Brighton to London is still £800 a year cheaper than the route “Any Permitted” fare, even though Thameslink is arguably now the best rail service in Britain. Had Brighton not had competition and seen just industry average growth, there would have been 1.5 million fewer passengers per year; or 4,000 fewer per day - and those 12 car trains would not have been needed.

The accidental cliff edge

The West Coast Mainline capacity crunch was also driven by an unintended facet of the fares system. In this case, it is the fact that prices were anchored in British Rail’s 1993 fares. Back in 1993, the West Coast Mainline was the shabbiest of Britain’s mainline railways. Some of the trains dated back to the 1960s and the maximum speed was lower than on either the East Coast Mainline or the Great Western Mainline. As a result, British Rail priced the tickets lower; reflecting the worse competitive position against car, coach and airlines.

Lower fares for slower, older trains: the West Coast mainline in the 1990s

By the middle of the noughties, however, the line had been entirely upgraded. Yet the saver ticket was still anchored to its 1993 British Rail fare. To compensate, Virgin Trains disproportionately increased the walk-up Anytime fare, thus creating the famous Euston ‘cliff edge’ when the price suddenly collapses at 7pm (and what feels like half the population of London attempt to board the next train). The obvious solution is to disconnect the price of the off-peak ticket from the 1993 British Rail price point but that contravenes the entire basis of the fares system.

Where we are today

Train fares are a mess. Britain’s largest train operator (GTR) has never taken revenue risk, so has always been entirely disconnected from the need to set sensible fares. That might explain why the day return for a family to Plumpton is unaffordable for most families. Indeed, had someone at GTR wanted to reduce the price to the South Downs for families, they probably would not have been permitted to do so, as DfT takes a formulaic approach to pricing as opposed to a market-based one. The same is now true of every operator. Even when operators did take revenue risk, the constraints of the system frequently prevented fares from being used in a way that worked.

The problem with reform has always been that changing fares inevitably means increasing some.

But Covid creates a real opportunity: for the first time, demand is low and there is spare capacity. It’s therefore possible to reform the fares system without needing to protect existing revenue to the same degree, as the existing revenue base has already been eroded. And spare capacity creates an ability to achieve growth by cutting fares as opposed to putting up prices: which is a much easier sell.

So now is the moment to change!

Some of the thinking’s already been done

Moreover, we don’t have to start from base principles, as RDG proposals exist, have been on the DfT’s desk for two years and come with the endorsement of Transport Focus, the passenger watchdog. They’re deliberately vague in places but the fundamental point (we’ve got to change the way fares work!) requires Government engagement.

The RDG proposal is to move to a single-leg pricing structure for the whole rail industry, with regulation of overall prices paid as opposed to regulation of individual ticket types.

RPI+x on individual fares ties tickets to the 1993 British Rail fares forever. Regulation should be focused on the goals Government is looking to achieve - which is consumer protection. The proposals suggest overall caps, possibly across a day or a week. This will address the ‘cliff edge’ problem described above.

The proposals also recognise that a lot of the complexity occurs where different fares rub up against each other. This is partially a facet of the fact that every station has fares priced to every other station. But is this really necessary? Urban area networks can be treated separately from intercity networks. Do we really need fares from Kenton to Hazel Grove? Kenton to Watford, yes. Watford to Manchester or Stockport, yes. Stockport to Hazel Grove, yes. Combining all these different tickets back into one bundle for the customer is a distribution problem.

So implementation of the technical and regulatory proposals already made by RDG and ignored by Government is an essential enabler. The problems that exist within the existing pricing system cannot be solved until these changes are made.

However, making these technical changes will not automatically mean that anything gets better. Assuming that because you fix the fares system means you’ll get better fares is like assuming because you fix the hoover, you get a cleaner house.

I’m afraid, you still have a lot of hard work to do.

Don’t worry about complexity

In thinking about the work you do have to do, it’s also worth being clear on what doesn’t need to be a focus.

The RDG proposals, very sensibly, don’t attempt to create new constraints on what fares can be charged. It leaves open the possibility of prices varying considerably on different trains, at different times or in different regions. This is absolutely right: as there’s nothing inherently complex about lots of prices; the problem has always been the distribution problem of a retailing system that pushed all the cognitive effort onto the user.

“Complex fares” has become a synonym for “poor distribution” with the result that people try to solve the wrong problem.

As an illustration, TfL virtually eliminated complaints about fare complexity through the introduction of Oyster.

The fact that, under the hood, there are still all kinds of crazy complexities (different zonal fares according to whether your train is priced by TfL or a train operator, peak and off-peak fares, different fares for different routings, etc). If I type one of my favourite day-trip destinations, Richmond, into the single fare finder from Walthamstow Central, TfL’s fare system gives me no fewer 11 different adult single fares - and that’s before we look at the 8 possible categories of discount).

But TfL doesn’t get criticised for fares complexity in the way National Rail operators do, not because the fares aren’t complex, but because TfL’s distribution system eliminates the cognitive effort required.

If, in advance of my trip to Richmond, I had to look at those 11 fares and work out which one I wanted and then commit to it (knowing I’d be fined if I strayed off the commitment I’d made in advance), I’d find it exhausting and stressful. But, I don’t. I know the rough rules (go via town = cost more, go in the rush hour = cost more) and beyond that, I can just set off.

The criticism of rail complexity originates from the period in the noughties when the combination of advance fares and online retailing were incentivising users to make their own bookings, but the distribution systems forced the poor user to work out for themselves what every fare meant: knowing that a man in a peaked hat would whack them with a fine if they got it wrong.

Here’s what the Trainline app shows me for a search from Leeds to London for a 9AM arrival on Wednesday 5th May. As you can see, Trainline have made a pretty decent fist of taking all the complexity of the fares system and presenting me with a simple price for each option:

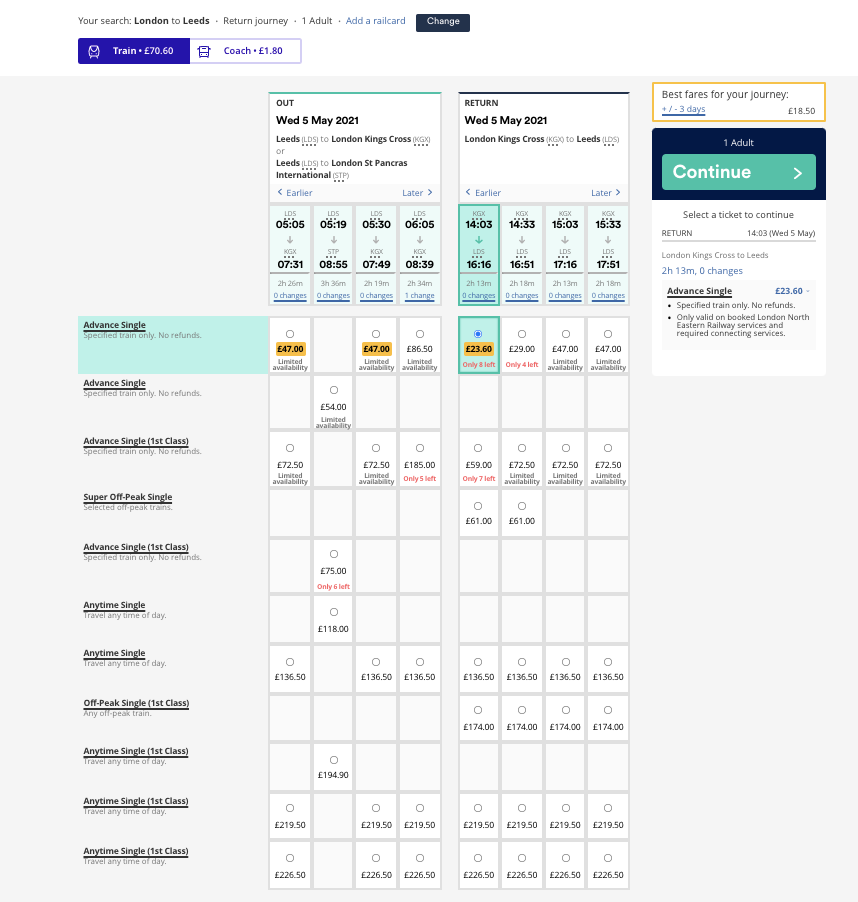

But the Trainline app is comparatively recent. Train fare complexity became ‘a thing’ when Trainline was a baby. Buried within the bowels of the Trainline website, you can still see tickets presented using their original selection format. Here’s exactly the same search presented using the original format:

That is absolutely terrifying! A poor customer confronted with a grid like that is obviously going to scream that the fares are complex. But it’s not a fares problem. Fares shouldn’t try to compensate for distribution failings as all that will do is create more circumstances in which the fare being charged is wrong for the market in question.

What next?

Once the technical and regulatory issues are fixed, it becomes possible to charge sensible fares.

But fares aren’t a thing in their own right - fares are simply prices; and price is one of the most fundamentally important decisions for any business. So you can’t solve fares by looking at fares; you have to look at the incentives for operators.

I’ve covered a lot of this before, so I won’t repeat them in detail here. You can read about incentives here.

But two key principles need to be adopted if train fares are going to work for users:

1) Target growth. If Britain is going to meet its Net Zero obligations, more people are going to have to go by train. Network Rail are already talking enthusiastically about taking advantage of reduced demand to make the trains run on time by running fewer of them. While this might be the right thing to do in certain specific locations at certain specific times (e.g. peak capacity into cities between 8 and 9 if the traditional commute changes), in general, the railway should measure success through more journeys.

If we’re targeting growth, we’re not going to end up with the situation that caused rigid fares regulation to be created - the risk of railway managers ‘pricing off’ demand.

2) Think local. Fares reform is often a national project imposed from the top. But ‘the railway’ consists of lots of markets. As per this post from earlier in the year, there is no need to manage any aspect of the railway (including fares) in urban Manchester in the same way as the Cornish branch lines or the intercity route from Leeds to London. A fares strategy should therefore be a localism strategy, designed to empower local business units to maximise growth the ways they know best.

It’s only through locally empowered management teams searching out every last opportunity for growth that the railway is going to maximise its potential. At the moment, there is literally no-one who cares that it’s unaffordable for a family to go to Plumpton by train for a country walk, even though the seats are available to carry them. That needs to become someone’s obsession.

Don’t miss the opportunity

Williams is due imminently. That statement has been true for years, but all the indications are that DfT are just going to avoid the wait for Williams moving into four figures.

Depending on when you start counting, we’ve currently been waiting about 960 days. If they get it out before mid-June, the wait will avoid the nice round thousand. (For comparison, Operational Overlord, otherwise known as the Normandy landings, were planned from scratch in about 390 days)

Addressing fares along the lines proposed two years ago must be part of it.

But it must also create empowered, commercially-minded management teams with local focus and strong incentives so that fares become a focus of business strategies targeted on growth.

The future of both the rail industry and Britain’s Net Zero targets depends on it.