Why Open Data is Crucial to Growth

Open data is the most important thing happening in buses right now. But this must be only the start

In 1987, the big European airlines came together to create “Amadeus”, a global distribution system for their fares and ticketing data.

What a shame that it’s taken 34 years for the bus industry to catch up, and an even bigger shame that the bus industry didn’t emulate their airline cousins by making it happen together, but instead left it to the DfT to lead.

That’s a shame for two reasons; firstly because DfT isn’t the right place for the project to live.

Secondly, because open data is hugely important for the future of the bus industry, and it would be much better if the industry were ‘doing’ not feeling like it was being ‘done to’.

Nevertheless, 7th January marked an important milestone: the deadline for operators to provide open fares data. Finally, one of the most extraordinary failures of the bus industry will have been addressed: the complete inability for customers to find out how much a bus journey will cost without actually making the bus journey itself.

But fares and timetable data only scratches the surface of what needs to be done to make the bus market work.

I know nothing

To explain, let’s imagine that I want to get a meal in my local area. As soon as I start to think, I can immediately visualise my options. I know about the posh-but-pricey restaurant, the cheap and cheerful Italian, the kebab takeaway and the coffee bar. I can visualise all of these because I walk past them. Because I can see their fascias, their fonts and glance in at their windows, I can immediately get a sense of what they’ll be like. As a result, I can make a purchasing decision easily and accurately, based purely on information I’ve absorbed subliminally through going about my business.

Now let’s imagine I want to make a journey to a nearby town. What information will I have gathered from walking the streets? Well, I may know there’s a bus stop. I’m highly unlikely to know whether there’s a relevant bus and I’m fantastically unlikely to have any quality or price yardsticks. As a result, I’ll probably drive.

Now, this is no-one’s fault - it’s just a difference between cafes and buses.

But it’s a problem if you want a bus market to work properly.

Buses share many characteristics of online businesses: no street presence means incomplete information.

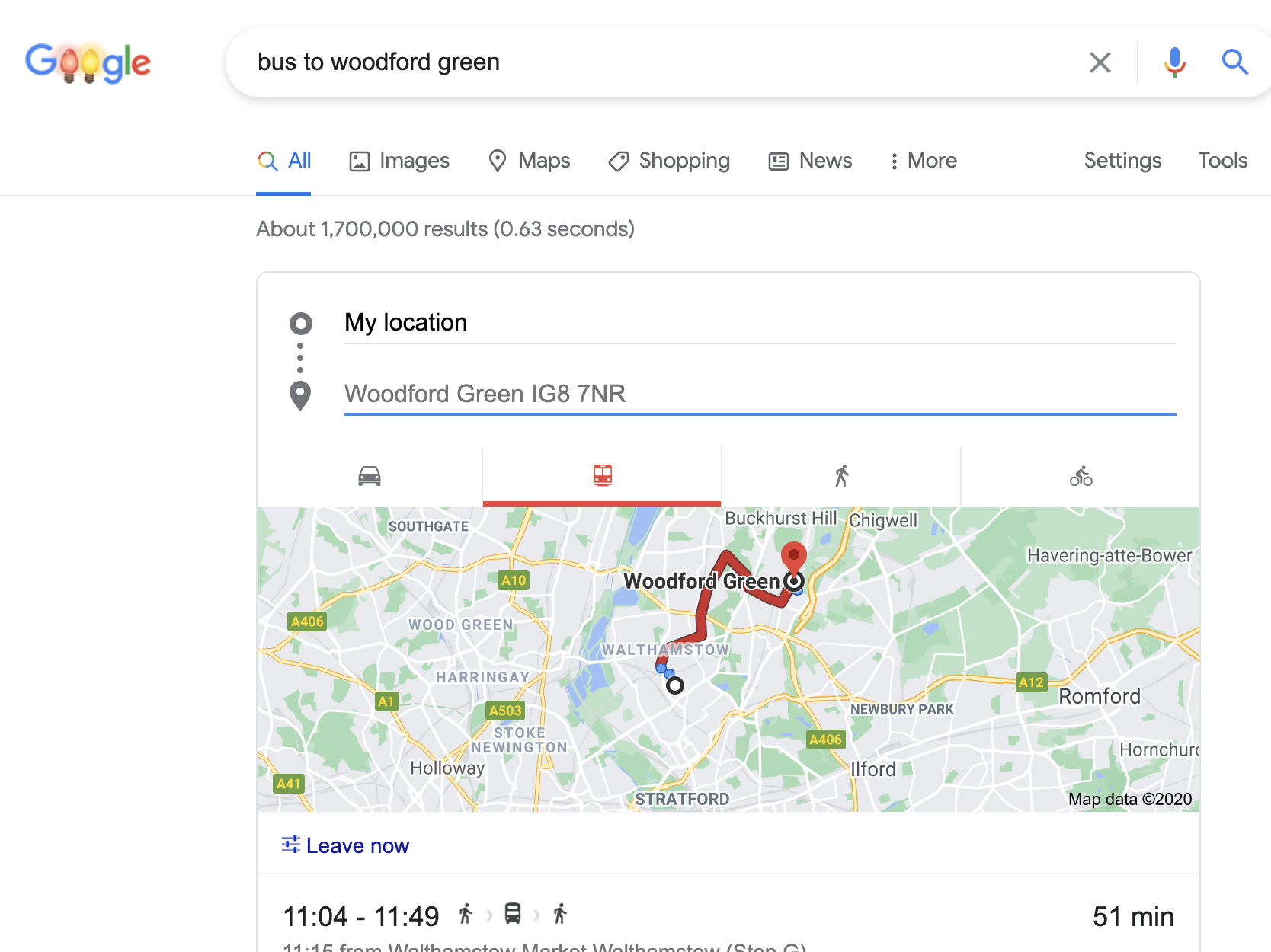

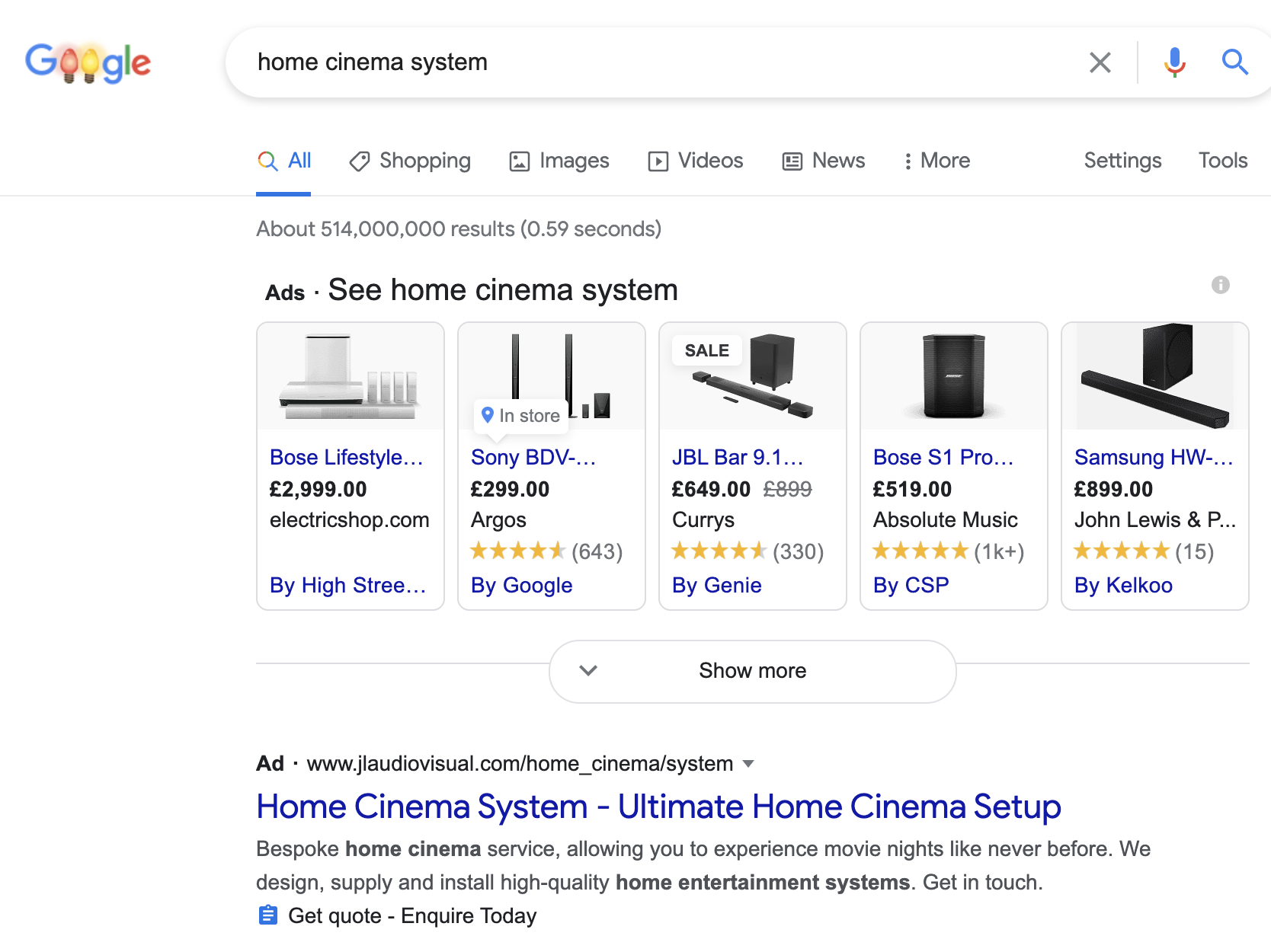

Let’s imagine, therefore, that I want to buy a new home cinema system online. I do a search and within 0.59 seconds, I immediately get a whole range of different options presented to me: priced and quality-rated.

Now let’s imagine I want to search for a local bus ride. In 0.63 seconds (damn that extra 0.04 of a second!) I get presented with a detailed map showing the itinerary and route of the bus. It shows me where to board and what time it runs. It’s absolutely brilliant and dramatically reduces the friction of getting a bus compared to 20 years ago.

The British Restaurant of buses

But do you see the problem? It’s very much ‘a bus’. There is absolutely no way to gauge quality or price information, meaning I must assume the worst of both.

In that context, the only rational behaviour for a bus operator is to use a bog standard bus at a bog standard price. With that, you’ll get a relatively small market share.

(By the way, I don’t mean that with open data buses will automatically be more premium. Some will, but there could also be a market for lower cost buses in some places, if people knew they existed).

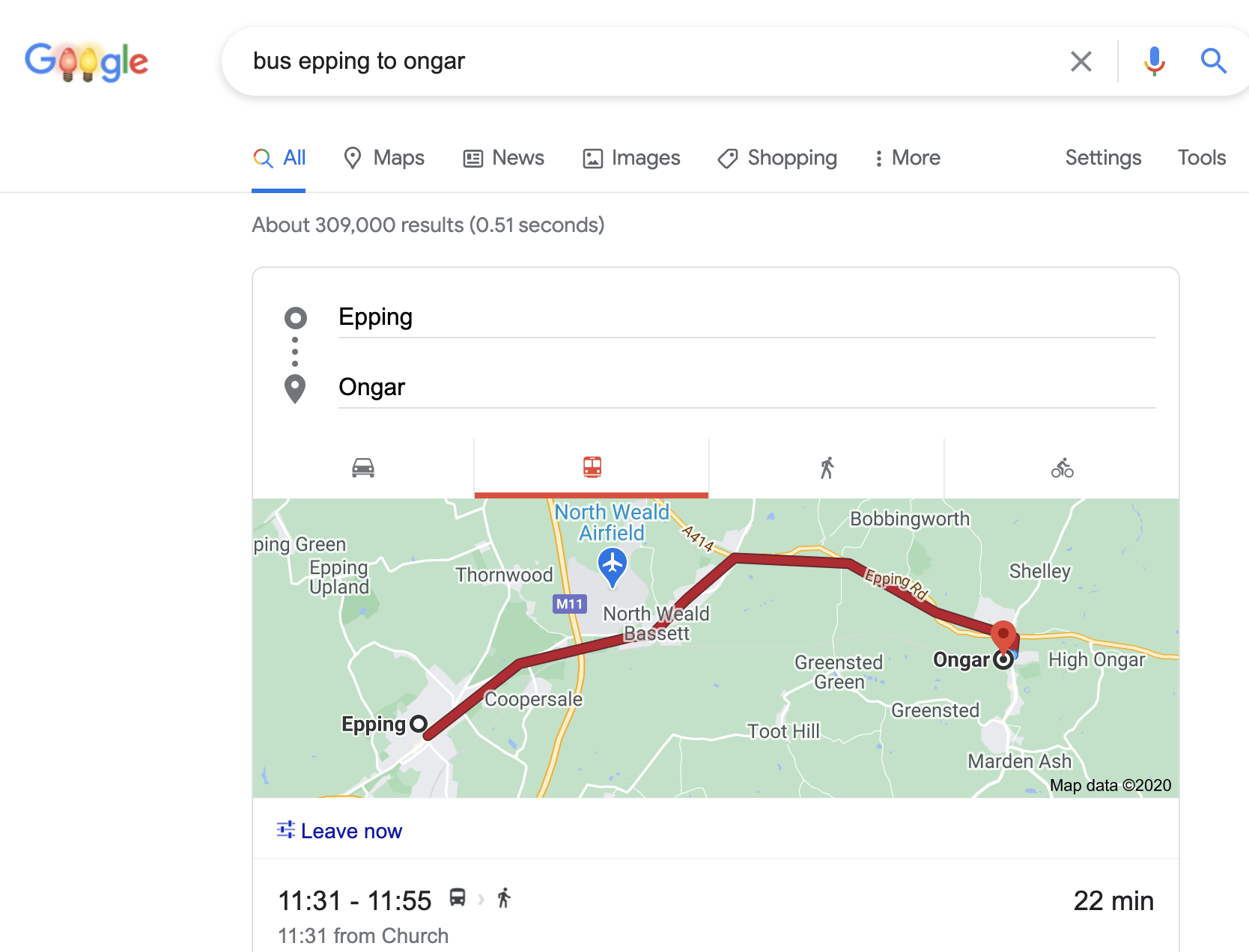

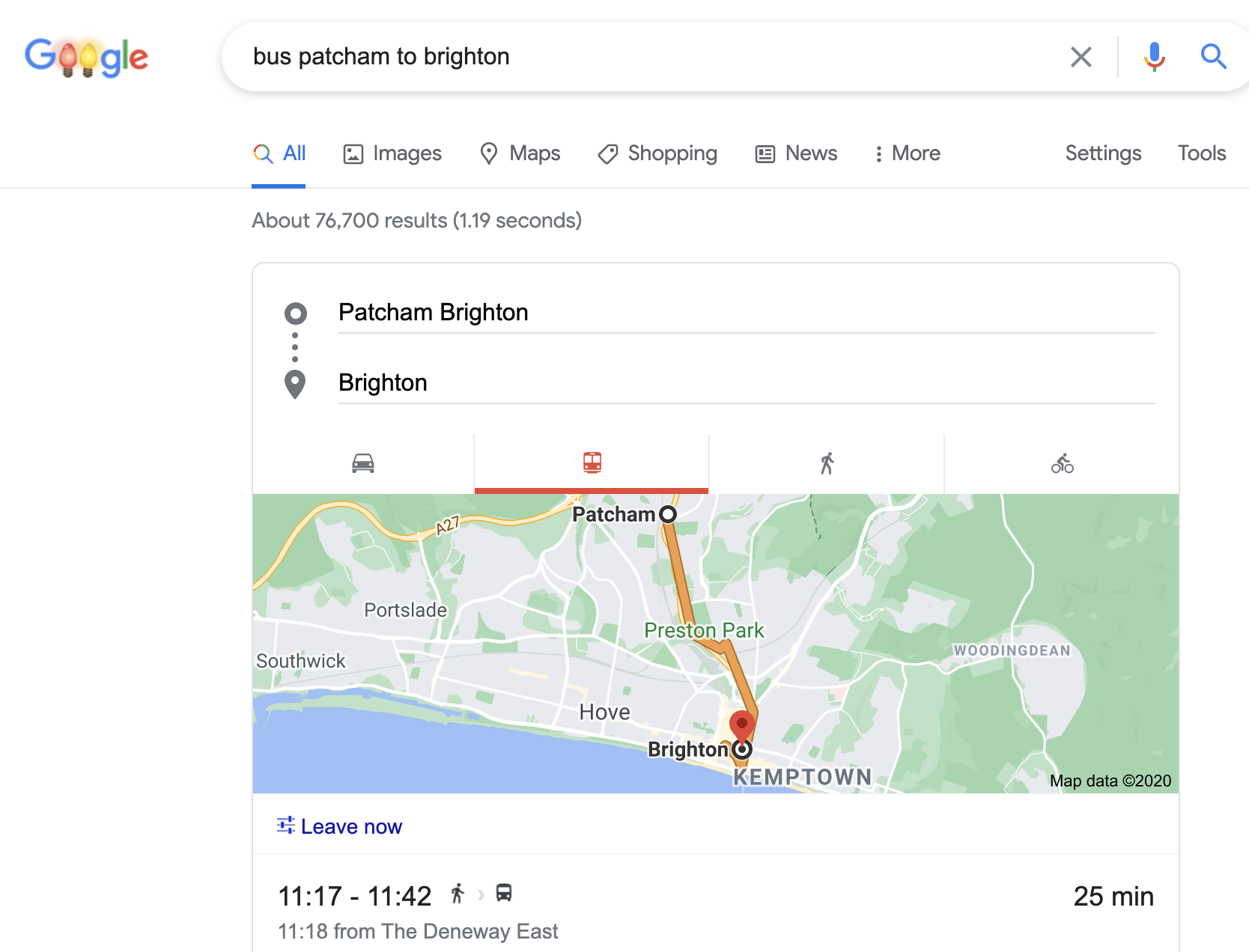

This is how Google presents information about, for example, the 22-minute ride on the 420 bus from Epping to Ongar and the 25-minute ride on the 5 bus from Patcham to Brighton.

It does tell me that the 5 is more frequent.

It doesn’t tell me that the 5 runs largely on bus lane, so is likely to be reliable whereas the 420 is on a rat-run off the M25 and is chronically unpunctual. It doesn’t tell me that buses on the 5 are clean and have wifi whereas the buses on the 420 are generally grimy and do not. It doesn’t tell me the fare, or how likely the bus is to turn up at the advertised time or how I can pay or anything much.

Without actually boarding a bus, the information available is simply that there is a bus.

This is the equivalent of a restaurant market in which the only information available before entering is that there is a restaurant.

In such an environment, no-one would ever create either The Ivy (as the tiny number of people who wanted such a product would never find it) or Happy Kebab (as too many potential customers would walk out when they saw the grease). Even though there is a market for both of these.

Instead, the entire restaurant market would come to resemble the wartime British Restaurant: basic if boring food at moderate prices.

Plain and simple: the basic British Restaurant

© IWM. http://media.iwm.org.uk/ciim5/34/488/large_000000.jpgThe bus market that exists today is, basically, the British Restaurant of buses.

Here’s what you might have won

Off the top of my head, here are some features that bus operators might offer, were it possible for consumers to discover their existence and make a choice as to whether they wanted them:

Punctuality guarantees

Faster journey times

Journey time guarantees

Better waiting environments

Park and ride sites

(I have deliberately not listed wifi and leather seats! It’s great that some buses now have wifi and leather seats but it’s not a panacea. It’s not even close. The fact that the bus industry thinks that a ‘premium’ service is one that offers wifi and leather seats is a bit like a restaurant that stops caring about either the price or ingredients of the food and thinks that success will be built on upholstery.)

The reality is that journey time, punctuality and price are the things that customers care about: everything else is a nice-to-have.

Give consumers the chance to choose

Put yourself in the shoes of one of the circa 50% of Brits who never get a bus. Imagine you’re considering a bus ride for the first time in decades; probably since you were a kid. You've discovered there’s a bus stop at the end of the road and where the bus goes. But if you have no idea if it’s likely to turn up on time or how long it will take (I don’t mean the timetable: I mean how long it will actually take!), you’re highly unlikely to give it a go.

By contrast, knowing some basic ‘hygiene’ facts (95% of buses on this route were on time last year, the journey time took less than 20 minutes on 90% of occasions) would give you a lot of reassurance.

This means that reliability data needs to be published alongside actual journey times.

And isn't it extraordinary that (unless I’ve missed it) there is no database of bus lanes and bus priority measures; despite use of bus lanes being a key competitive advantage of buses where they exist.

The bus data should also include the soft features that aren’t crucial but are still important. Wifi, charging sockets, the ability to take cash and give change, the ability to accept different smartcards and the quality of waiting facilities. All these are things that could make the difference to a passenger’s choice.

Remember, the purpose here is simply to get give the consumer the knowledge to make an informed choice; as they already have for other local services simply by walking around.

So the priority should be information. This means:

Fares data (which is decent work in progress)

Punctuality data (which, like all the others below, is not, though it can be extrapolated from location data)

Reliability data (other than limited, by extrapolation)

Bus priority

Actual journey times data (other than limited, by extrapolation)

Service quality data

Eventually, it may be that some of this will become organic (in the way that there is no central database of restaurant quality: Google relies on users for this) but something needs to be the catalyst.

Now, some operators may complain that this is bureaucratic. Why share all this information? Will anyone actually use it?

Well, it is bureaucratic if it is mandated by the Department for Transport. The fact that DfT has had to step in and mandate open data is a real failure on behalf of the big five transport groups. After all, Amadeus (the industry-leading fare data source for aviation) was created by a consortium of major airlines in 1987. If the ‘big five’ aren’t going to lead on projects such as this, why do they exist at all?

Indeed, the fact that it has been mandated by DfT suggests a rather depressing way of thinking within the current bus corporates. The fact that, currently, operators tend not to provide this information (even via their own apps and websites) is rational in a declining bus market. If users already know the offer, there’s no incentive to expend resources on mythical new customers that never come.

We now have a scheme and, unlike in virtually any other industry, it is being run by Government. It’s not the right place for it. Central Government is too distant from the end user and the culture of Whitehall is not conducive to good results for this kind of project. If the industry stepped in to do a better, more comprehensive job, they would immediately earn the respect that corporates are going to need in a world in which re-regulation is being examined across the political spectrum.

Obviously smaller operators are key to this scheme as well, but they are the ones least likely to have the management resources to take on a new data input task. So smaller operators should have their costs generously reimbursed. There are currently 500 operators providing bus services in the UK: if the average reimbursement was £20,000, that would comfortably cover operators’ costs, ensure that the data was actually decent and cost £10m: just 4% of the reduction in local authority support to bus services in the last 10 years. Given this scheme has landed with Government, this should be a small price to pay for doing it properly.

And the consumer impact would be huge. Put yourself back in the shoes of the 50% of the population that never go by bus. Now look at this Google Maps search result as it could be with proper data:

How much more reassuring is that?