The ringways that nearly destroyed inner London

When I was growing up, my parents used to sometimes tell me that ‘they’ nearly knocked down our house to build a motorway.

I didn’t really take much notice. (They were my parents. One didn’t. Now I am a parent, I regret this).

But when I grew older, I looked into what they’d been going on about.

It’s a salutory reminder of why we need to keep reminding the world of the need for outstanding public transport.

Predict and provide

In the 1960s, highway planning was dominated by the idea of ‘predict and provide’ - work out how many car journeys there will be in ten years time, and then build the roads needed to accommodate them. As car ownership was growing and public transport was not, London’s highways planners kept predicting they’d need more roads.

So they set about providing them.

The Ringways

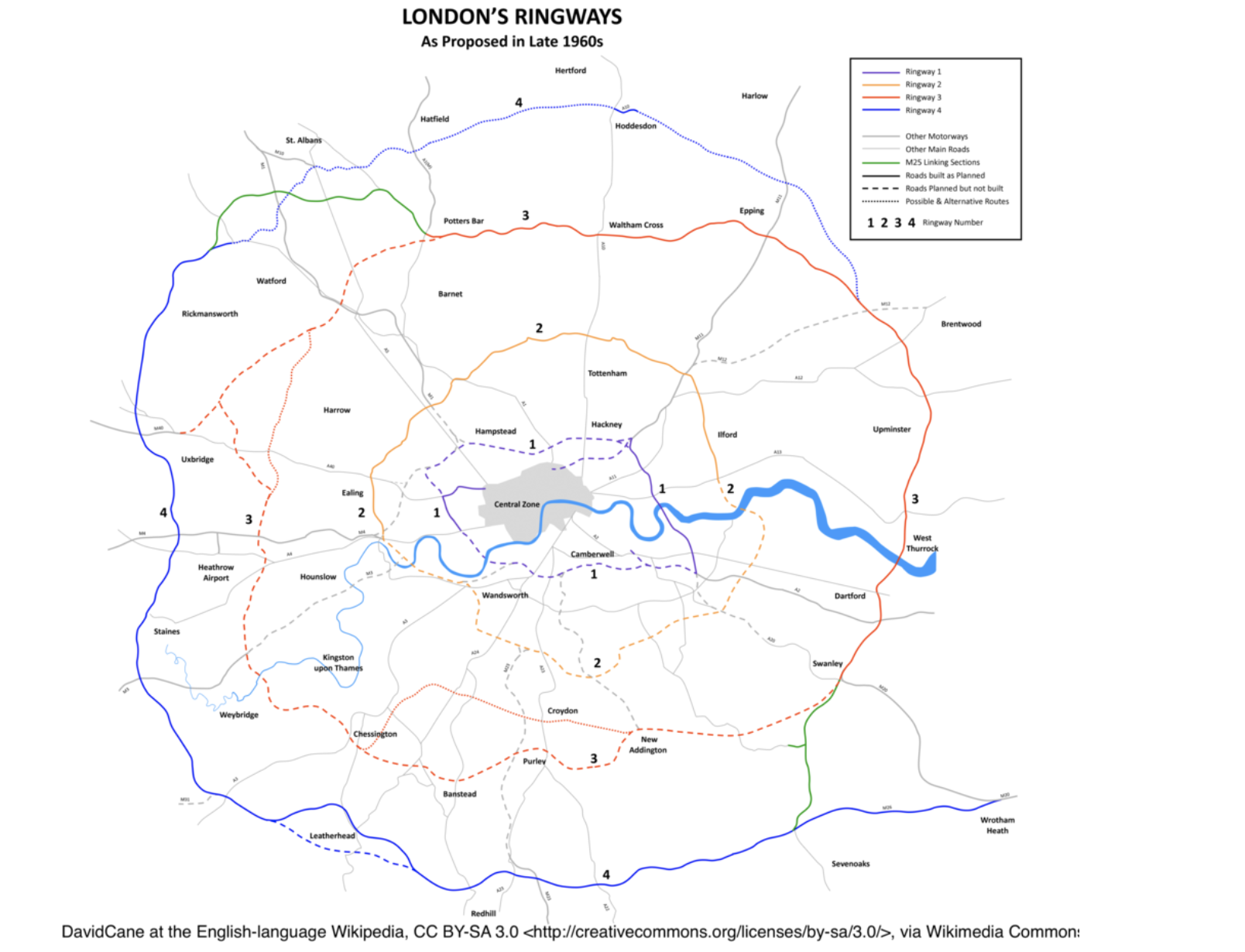

This map looks so simple and innocuous, but it shows the plan that was developed in detail and started.

It shows four circular ringways, all motorway-standard, plus radial connecting routes. You see that “1” marked on the map between Hampstead and Hackney? That’s roughly where my parents’ flat still is - but wouldn’t have been.

The dotted lines are the motorways planned but never built. Map: roads.org.uk

Just let me list some of the places that would have been destroyed had this happened. Camden Town, Hackney Central, Oxleas Wood, Clapham High Street, Brixton , Blackheath Village, Peckham Rye and Kings Cross. My parents’ flat in Chalk Farm was in a modern, pretty ugly block, so certainly wouldn’t have been mourned by anyone. But they love it!

Have you been to Dalston at all? Here’s what it would have looked like had this plan happened:

Dalston Junction (no, not that one!). GLC, January 1967

What about Camden Market? You know the famous Stables Market? The one that tourists from all over the world visit? Well, it’s completely buried by the junction of Chalk Farm Road, the North Cross Route motorway and the Euston bypass.

Think the Northern line’s complex? Think again… Map credit: roads.org.uk

While this artists’ impression of the new, improved Brixton shows how in thrall planners were to an American vision of urban modernity:

Brixton town centre as you’ll never see it. Photo of Lambeth Council document by Chris Marshall at roads.org.uk

There but for the grace of… people like you

Now, I know what you’re thinking: “Loads of crazy stuff was planned in the 1960s. This was never actually going to happen. After all, this is the same decade that they planned to cover the whole of Soho in a glass roof.”

Well, you’re right: that Soho glass roof thing was probably never going to come off. Though it was planned.

But the truly terrifying thing about this was not just that it was going to happen, but that they actually started!

Look carefully at the non-dotted bits of the map at the top and you’ll see some bits of road you recognise.

Ever wondered why there’s an elevated section of the A40? And why there’s just one completely random section of dual-carriageway that goes south from the A40 past Westfield and then suddenly stops at Shepherd’s Bush Roundabout. Well, that random section used to be a full-width motorway and was the first section of the ringway built. And the elevated section of the A40 was the first section of radial built.

Here’s a picture of the junction at White City, just after it was opened:

Ever wondered why this whole roundabout is on stilts? Because as well as a motorway going East-West, there was also meant to be one going North-South, at ground level.

Do you see that the stubs coming off on the right-hand side? They were the start of the slipways leading from the roundabout onto the motorway that was then going to snake through Kensal Rise Cemetery, under Belsize Park, through Camden Town, Islington and Hackney and wind up near Victoria Park.

Those stubs are still there; a reminder just how close we got to destroying vast swathes of London’s most beautiful neighbourhoods.

At Victoria Park, we then have another long length of ringway that was actually built before the plans were pulled. The section of road that is now the A12 north of the Blackwall Tunnel and the A2 south of the Blackwall Tunnel were actually the Eastern side of Ringway 2.

I stood on the footbridge that links Victoria Park with the Olympic Park with my daughters a few weeks ago. This is the view:

You’re looking north along the A12 here. The reason for the big space in the road with trees? Because that’s where the motorway from Hackney, Camden, etc should have merged into what is now the A12. You can literally see where they’d got to when the bulldozers stopped.

The sections of ringway that were built opened in 1970. One year earlier, a report had revealed that 1 million Londoners would have their homes ruined by living within 200 yards of a motorway. The report also made the obvious point that all the capacity of the motorways would never be used, as they’d be overwhelmed by congestion at the junctions when thousands of cars attempted to navigate onto narrow residential streets.

The sections opened in 1970 turned out to be the last. But the Greater London Council (GLC) continued to promote the scheme, and when Ken Livingstone was elected in 1981, he found a team of people still working on the project.

Since then, I’m delighted to say that while new roads have been built in London (the Limehouse Link, the A12 through Leytonstone, the Coulsdon Relief Road), many more new railways have been built. We’ve since gained the DLR, the Jubilee line, the East London line of the Overground and will (one day!) gain Crossrail.

But the fact that we can go through this collective madness is a reminder that collective transport wasn’t the obvious answer once and won’t be again. Be ready!