How Much Does Franchising Cost?

A post about the pros, cons and costs of bus franchising

I have spoken previously on this blog about my belief that our obsession with public v private is a distraction from the more important work of making services better.

Early in my career, the default assumption was private good, public bad. Now, that has been reversed. But it’s never as simple as that.

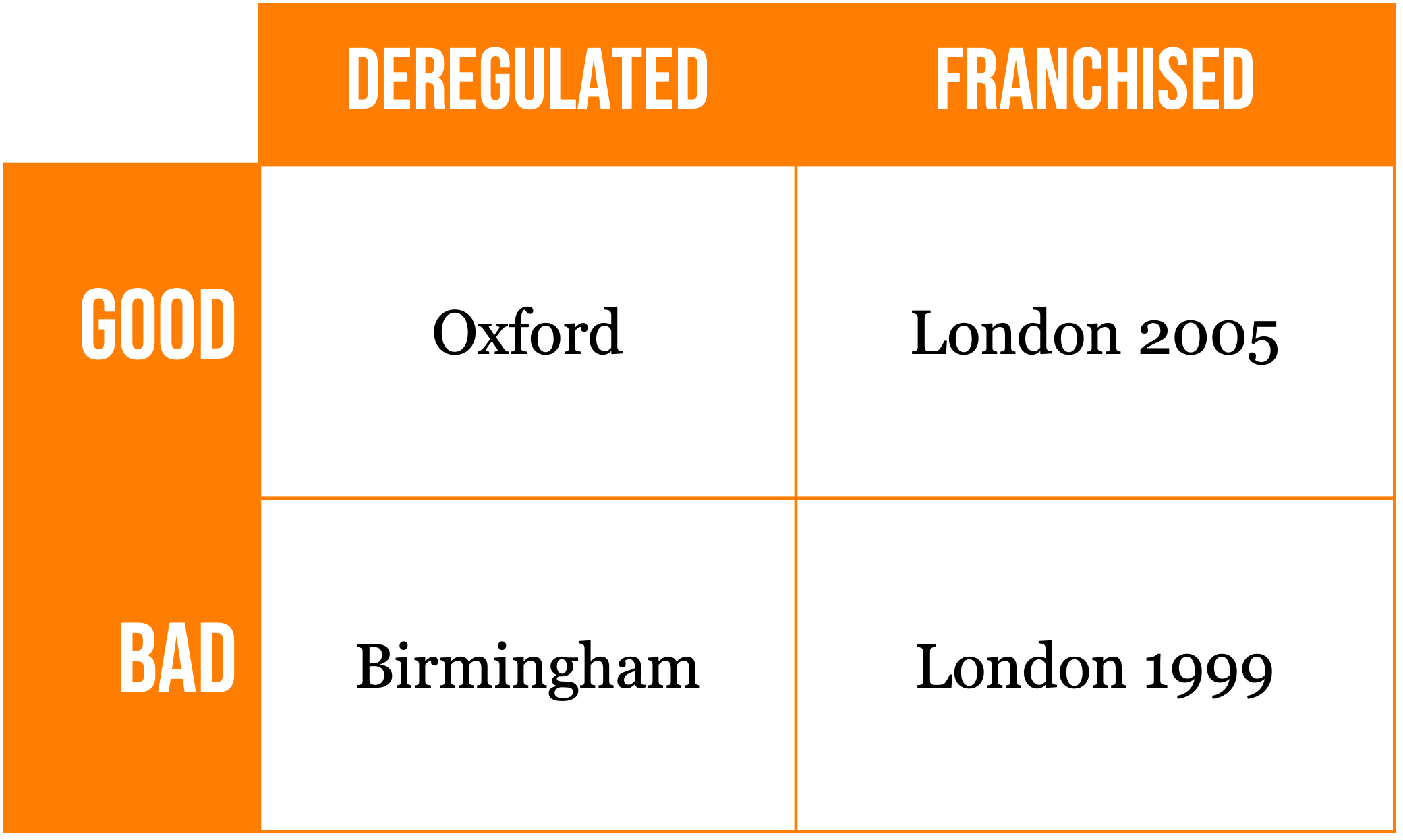

In 1999, when I went up to university, I moved from a city (London) with old, grimy, unreliable buses to a city (Oxford) with smart, modern, reliable buses. The former were privately operated but publically specified (what we would now call franchised) and the latter were fully deregulated. In 2002, I moved to a city (Birmingham) with a deregulated bus network being squeezed for profit and then, in 2005, back to franchised London - which now had a resurgent bus network.

Quality and operating model didn't correlate in the first four places I lived

As the four-box model of my experiences in the first four places I lived shows, there was no correlation between the model by which buses were delivered and the quality of the service I experienced:

Plenty of work has been done that shows what drives bus useage. If you want a simple guide, I cannot recommend highly enough this episode of The Freewheeling Podcast, in which James Freeman describes in simple detail his recipe for success. (If you don’t like audio, a write-up is here).

He’s relevant as only four local authority areas saw bus patronage grow in the decade between the start of austerity in 2010 and the Covid pandemic of 2020, and James was - at one point - in charge of three of them. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the places that did it right ranged from deregulated (Brighton and Bristol) to publically-owned (Reading).

The recipe for success is leadership, delivering the basics and good-quality local marketing.

Franchising for all

Despite the paucity of evidence that changing the ownership model is the silver bullet, the change of Government has caused a swing in the ideological pendulum. Under the Tories, local authorities were actively prevented from setting up their own bus services, despite the evidence from places like Reading and Nottingham that it could succeed. Under Labour, local authorities are being encouraged to take more direct control, with franchising being the preferred option.

I’m not going to argue that franchising is either ‘good’ or ‘bad’. What I am going to do is say that we should be clear that it has costs and benefits: and we should be explicit about what they are.

Why Franchising?

Franchising is designed to deal with the biggest challenge of a deregulated bus network: the lack of a single, comprehensible network. Deregulation has worked best in places like Brighton, Oxford and Nottingham where one or two operators work closely with the local authority. Places with highly fragmented bus operations have seen a plethora of different ticket types, fare levels and marketing materials, making it difficult for a consumer to navigate the network as a network.

Bus franchising can ensure that all buses look the same, charge the same, accept the same tickets and that the network is planned as one. The poster child for this model is London, which has operated in this way since the 1990s.

Manchester, by contrast, had a highly fragmented public transport network. Train services between Stockport and London are provided by four different train companies, with two major bus operators plus multiple smaller ones. Compared with the clarity of the century-old Transport for London brand, transport in Manchester looked confused and cluttered. Bus use declined.

On 25th March 2021, the Mayor of Greater Manchester, Andy Burnham, officially decided to introduce a bus franchising scheme for the entire Greater Manchester Combined Authority ('GMCA') area. The GMCA is the contracting entity and the bus franchising scheme will be overseen and managed by Transport for Greater Manchester ('TfGM'), including the procurement of franchise operators, on behalf of the GMCA.

Transport for Greater Manchester set out a vision for an integrated ‘Bee Network’, which would:

▪ Bring together bus, tram and active travel by 2025 (with commuter rail to follow by 2030).

▪ Deliver a transformation in the way people travel, with integrated fares, customer information under a single, identifiable and accountable brand.

▪ Support people and places to thrive, as well as the sustainable delivery of new homes and employment.

I spoke to Vernon Everitt on The Freewheeling Podcast, and he talked me through their vision with great enthusiasm. You should listen.

Manchester History

There’s a reason why Manchester was first out of the blocks when it came to franchising: it long had an unusually fragmented bus service. Its great rival as Britain’s second city, Birmingham, has a single, dominant bus operator. (when I was a kid, Birmingham was unambiguously Britain’s second city, but I don’t think you can say that today). During my time there, Travel West Midlands was pretty woeful. But Andy Street, as Mayor, built a co-operative partnership. Only one deal to be done.

Like in Birmingham, Manchester used to have a single, public-sector bus operator, owned by the city. But in 1993, it was split into GM Buses North and GM Buses South. The idea was that, once privatised, the two operators would compete with each other, creating a dynamic, customer-focused bus marketplace.

But that’s not what happened. In practice, both stuck to their original operating patches, but went in very different strategic directions.

As the 1990s progressed, GM Buses South ended up part of Stagecoach, while GM Buses North was bought by First. Stagecoach, under the entrepreneurial leadership of Brian Souter, grew its business. Fares were cut and new products were invented, such as Magic Bus - a new student-focused proposition, offering low fares on old buses.

First, under the… how can I put it… less entrepreneurial leadership of Moir Lockhead, put the fares up and cut investment. The city ended up with a mess of fares and brands.

By the way, if you want to treat it as a natural business school experiment, First ended up splitting the old GM North operation three ways. By 2022, the business was generating almost no profits at all (£0.7 million in 20220). All but its Oldham operation was sold to Rotala and Go Ahead for - as far as anyone can tell - significantly less than they paid for it, in real terms. By contrast, Stagecoach Manchester was profitable enough for Brian Souter to lead a doomed fight against franchising to preserve and protect its existing profits. In 2022, Stagecoach in Manchester earned £16m of profits on £110m of turnover.

Franchising

I’d like to tell you that franchising emerged as a result of the last Government’s desire to improve bus services.

But that’s not what happened.

In his book, Failed State, Michael Gove’s former special advisor Sam Freedman describes the genesis of the idea for creating Metro mayors. As he puts it:

“Osborne, ever the political tactician, also spotted an opportunity… He had London in mind, where Labour dominated central London but Boris Johnson had managed to win, and hold, the mayoralty through his appeal to the more Conservative suburbs”.

Sam Freedman interviews Rupert Harrison, who was George Osborne’s Chief of Staff at the time and really should know. He says that:

“The political argument was always well, actually, you know, in some of these areas, that’s the only way we’re ever going to win”

Having created Mayors, the Conservative Government then needed to provide them with some powers. The ability to replicate the London bus model, of which Boris Johnson was a huge advocate (he once claimed his main leisure hobby was making cardboard model buses), was an easy win.

However, the model only allowed regulation, not nationalisation. Cities like Greater Manchester, confronted with five bus operators of which four lost money, could probably have simply bought the operators for less than a quarter of the cost of regulation. Assuming that Stagecoach was the only business still making realistic profits, GMCA could probably have bought the lot for about £60m - a lot less than franchising was going to cost. But that option was not open to them. I mentioned earlier that of the big two, only Stagecoach was making serious money. Diamond and Go-Ahead were, respectively, earning profits of £0.9m and £0.4m on turnover of around £30m.

Franchising starts

The first tranche of the ‘Bee Network’ began on 24 September 23 (Go North West, Diamond), tranche 2 on 24 March 2024 (Stagecoach, First, Diamond) and tranche 3 is due to launch 5 Jan 2025 (Metroline, Stagecoach, Diamond, Go North West). Some of the school bus routes went to different operators.

Since March 2024, 324 bus routes – 188 routes in phase one and 136 routes in phase two – equating to around 50% of the bus network in Greater Manchester, has transitioned to management by Transport for Greater Manchester (TfGM).

TfGM is now undertaking Strategic Network Reviews to determine future changes to the bus network: exactly the kind of holistic thinking that was impossible under deregulation.

Fares & ticketing

The other key change that the Bee Network will provide is affordable integrated ticketing (integrated passes have been available for a while, but single-operator products were much cheaper). Tap and go is expected to be ready in March 2025, with unlimited journeys on Bee Network buses and trams from £7.80 a day off-peak.

A single bus fare costs £2, and a day's travel costs £5 (it is a coincidence that the £2 figure is the same as the national Government’s fare cap: the policies were arrived at independently). Children under 16 pay a capped £1 for a single, and £2.50 for a day's travel. A week of unlimited bus travel costs £21 for adults and £10.50 for children

How much is it costing?

Franchising doesn’t come cheap.

And it’s important to be clear how much it does cost to enable an informed view of whether it’s the right approach to take.

Unfortunately, the Manchester experiment has coincided with the Covid pandemic, the national fares cap and the Bus Service Improvement Plan era, making it harder to figure out what the precise costs of franchising are. I’ve found it somewhat challenging to piece the costs together, as they’re not conveniently located in one place. If colleagues from Greater Manchester are reading this, I’d really encourage them to produce a single report describing the costs of franchising so that other local authorities can make an informed decision.

Nevertheless, here’s my best attempt to figure it out.

The summary version is that the franchised network costs around £100 million a year more to run, and that set-up and capital costs have so far totalled just under £230 million.

Let’s go through it.

Running costs

Nominal prices. Values £. Source: Greater Manchester Combined Authority Revenue Outturn Reports 21/22 to 24/25

In 2021/22 TfGM spent £110m[1] on bus operations in and around Manchester (excluding early costs related to bus franchising). This year, it expects this total to be over £217m[2]. Very roughly, therefore, it looks like franchising costs an extra £100m per year. That’s not far off.

The costs in 2021/22

2021/22 is not a helpful base year, as it was also a Covid year. Local bus networks nationwide were supported by the Government to prevent mass bus route withdrawals. However, as these payments bypassed TfGM and went straight to the operators, let’s assume that - for the purposes of this exercise - 2021/22 is an acceptable starting point.

In that year, TfGM had two big cost elements for its bus network:

Tendered bus services:

£32 million was spent on tendered bus services. These are services provided by the local authority that the commercial operators do not provide but which are deemed socially necessary. They are often evening or weekend services on established routes, or low frequency routes to hospitals or suburban shopping centres. A historic challenge with tendered services is that they often ended up operated by a different operator to the dominant commercial operator in an area. This meant they would often not appear in information apps provided by the lead commercial operator, and - outside Manchester - sometimes would not accept tickets issued by the lead operator. This depressed the revenue earned by these services, increasing the cost to the local authority.

The cost of tendered services would be expected to disappear with franchising. In effect, franchising is ‘tendered services for all’, so the socially-necessary tendered mileage gets absorbed into a much larger tendered network.

Concessionary travel:

The other big cost was paying for concessionary pass-holders’ travel, which cost £78 million. This is a national scheme but for which the cost falls on local authorities. Elderly and disabled people get free travel, with their home local authority picking up the tab for their journeys, wherever they occur. As the vast majority of trips will be in Greater Manchester, this cost would also be expected to disappear with franchising.

So, in effect, the two big cost lines that used to exist will vanish when franchising is complete.

The costs in 2024/25

The new franchised network is still only 50% in place with a further tranche expected in January, so this year’s costs are a mixture of the old system and the new system. Given the proportions of the network converted and taking inflation into account, we would expect the tendered costs this year to be £13m and the concessionary costs to be £33m. Give or take a million here or there, that’s exactly what they are.

Tendered services:

While this year’s costs are in line with logical expectations, there is something interesting to note about previous years. Last year they rocketed from £36 million the year before to £67 million. What did that extra £30 million buy? It’s hard to be sure. In 2023/4, the early costs of the franchising scheme were accounted for as tendered services. So you’d expect the cost of tendering to be artificially higher. But it also seems like the cost of the existing tendered bus network went up. To explain, this revenue outturn statement tells us that

“From October 2022 operators gave notice of their intention to make commercial service changes across all areas of Greater Manchester in October including service withdrawals and reductions in frequency. Without intervention by TfGM the consequences of the service changes would be significantly detrimental in terms of accessibility to the network and accessibility for residents through the network to reach employment, education and key services such as health facilities. In response and following consultation with members of the GM Transport Committee, TfGM has replaced withdrawn services at current frequencies, with the exception of minor variants where there is no negative impact on network coverage. Where commercial changes involve frequency reductions, these were restored to current levels up to a maximum of four buses per hour.”

This make sense. Commercial operators maintain a network. But there will always be bits of that network that are marginal. They don’t make much money but it makes sense to keep running them for the good of the whole. If the commercial operators’ networks have no future, however, then it makes commercial sense to only operate the profitable core. This feels like a genuine cost of franchising which is worth future regions remembering as it will occur again. When budgeting for franchising, remember that there’s going to be a tendered cost ‘bulge’. It also may explain why franchising appears cheaper: the first year of franchising is always going to be cheaper than the last year of what came before.

Fares cap:

One thing that confuses matters somewhat is that the period of franchising coincides with the introduction of a fares cap. That means the cost of supporting the bus network has gone up. £17m is being spent on the fares cap this year but this only covers the cost of the non-franchised tranche 3 services for part of the year (from April to January, after which they will become franchised services). i.e. roughly half the network for three-quarters of the year. The rest of the fares cap cost is invisible, as it is swallowed into the overall cost of operating the franchised network. If franchising wasn’t a thing, then the full-network effect would be roughly £45 million. That is somewhat higher than last year’s outturn of £39 million for the fares cap but it’s in the same ballpark. So we can assume that of this year’s total costs of supporting bus services, around £45 million is supporting the fares cap, which could have been done without franchising.

Franchising net costs:

This is the big new line item in Greater Manchester’s accounts. The net cost of bus franchising is forecast to be £149 million this year. £28 million of this is the hidden fares cap costs (based on the assumption that the fares cap costs the same for proportionately for the franchised network as for the tendered network: which is a big assumption, but all we’ve got). Therefore the actual cost of franchising is around £120 million this year. If scaled up for the whole network, this would equate to £210 million for the whole network.

That means that the total cost to the public purse, excluding the fares cap, has gone up from £110m in 2021/22 to £210m. Adjusted for inflation, that’s an increase of roughly £90 million in today’s money.

There are roughly 180 million journeys per year on Greater Manchester’s bus network so, roughly, the taxpayer contributes around 50p for each to be on a franchised bus. As we’ll discuss shortly, this isn’t entirely accurate. Part of the challenge is that the period in which the franchising system was set up is one in which the bus industry has seen a substantial structural cost increase. Many of these cost increases would have occurred anyway, regardless of franchising. However, a proportion of the costs would have been absorbed by the operators and a proportion added to fares (which, if capped, would have been settled by the local authority). What proportion of that 50p would have been incurred anyway is very difficult to know.

Implementation costs:

Revenue costs:

There are also significant costs to setting up a franchising scheme. Greater Manchester have so far spent £47 million, excluding capital costs. These include the costs of ramping up a team to run the tendering process, consultancy support for setting up the scheme, branding and network design. In the accounts they are treated as exceptional items. But exceptional items still need paying for, so future local authorities need to be ready. Greater Manchester was ready: each year they have budgeted more than the eventual outturn.

Capital costs:

One of the big challenges Greater Manchester faced was in ensuring sufficient operators could participate in the market. This is a problem that the original bus franchising market, London, did not face. Franchising in London emerged from a fully nationalised network, not from a deregulated one. As a result, London Transport was able to engineer a competitive market by dividing its own operations into competing operators. Manchester started from a position in which the north and south of the cities each had a dominant operator. If they had simply issued tenders, the market would have been skewed. As a result, they decided to acquire the garages back from the operators. This was expensive.

In addition, there are other costs that were previously borne by operators but which become TfGM costs. The most obvious of these is ticketing. TfGM has big ambitions for an integrated ticketing system, which meant kit and computers needed to be paid for.

The total capital cost for the franchising scheme so far has been £180 million. While the revenue budget was judiciously underspent, there have been significant in-year overspends (30% last year and 90% expected this year). This isn’t because the capital works cost more. It’s because the bus tenders cost more, which meant that ticketing systems which were planned to be funded through the franchising revenue budget have instead had to be capitalised to create the space for the higher-than-expected costs of running the bus network.

These higher-than-expected tender costs are not a consequence of anything TfGM have done: it’s a function of the structural issues with the bus industry I mentioned earlier. Operators throughout the country have seen costs rocket in recent years as post-Brexit, post-Covid labour shortages have caused wage costs to go up, while raw material costs have increased engineering costs and battery supply chain issues has kept the costs of new vehicles high. The challenge for a local authority with franchising is that the operators are not obliged to take any of this cost risk. If every operator chooses to price their bids to cover their costs (and why would they not?), then all these costs are borne by the franchising authority.

Overall, then, it looks like the franchised network in Manchester costs roughly an extra roughly £100 million each year and has cost around £180 million in capital costs and £45 million in one-off revenue costs to set up. Over the first five years, it’s going to be around £700 million by my estimate.

So what is Manchester getting for its £700 million?

Benefits of Franchising That Can Only Be Achieved Through Franchising

Control:

The big benefit of franchising is control. TfGM can now set the times, set the fares and manage their network. It’s not absolute control: franchising involves issuing multi-year contracts, so it is much easier to make changes when contracts are up for renewal. As London showed with the Superloop, it’s not impossible to make changes mid-contract, but it’s easier and cheaper not to. If local authorities want this level of control, it’s very hard to achieve it without franchising.

Accountability:

Andy Burnham, as always, wearing his Bee Network badge. He is visibly highly accountable. Photo TfGM

Franchising makes it very clear where the buck stops: with the politicians. Andy Burnham has embraced this: he’s rarely seen without his Bee Network badge on, literally wearing his new accountabilities visibly. Franchising replaces accountability to customers through the fare box with accountability to voters through the ballot box. This might be helpful. Better buses can often require action that is outside the scope of a bus operator. For example, early in his first term, Ken Livingston introduced the Congestion Charge, which cleared street space for buses. Also, when politician feels accountable, will they do what’s necessary to make it better? e.g. congestion charge Manc v congestion charge London. By contrast, in 2008, Manchester also had a congestion charge referendum, but without the political accountability of a Mayor, and it was rejected. If there’d been a Mayor with a Bee Network badge, actively selling the change would the result have been different? Who knows. It’s notable that Andy Burnham shows no sign of testing the idea to find out.

Distance from operations:

One of the good things about franchising is that it gives politicians control and accountability, but it also keeps their distance from day-to-day operations. If you listen to my podcast, you’ll hear how passionate Bernt Reitan Jenssen (CEO of Ruter, Oslo’s transport authority) is about the transport authority (in this case TfGM) not directly operating the services, but contracting them out. You can see the difference it makes by seeing how much TfL gets drawn into industrial relations on the Underground (which is operated in-house) compared to the bus network or DLR (which are not). Bus franchising keeps the politicians from being able to get too involved in running the network: the services are still delivered by a professional bus company.

Benefits of Franchising That Can Also Be Achieved In Other Ways

Consistency:

It’s absolutely true that franchising can deliver a consistent network. Every bus in London is red, every bus in Manchester will be yellow. However, there may be other ways to achieve the same goal. In a future post we’ll talk about the work that Cornwall are doing. They are seeking a single Transport for Cornwall brand with a single Transport for Cornwall ticketing system and fare structure. I won’t get into detail now, but they’re making good progress towards their goal.

One of the biggest consistency challenges in a deregulated network has often been the interface between the commercial and tendered network. A passenger might buy a return ticket on a route at 1600 and then discover, when they come home at 1900, that the operator changed an hour earlier and their ticket is not valid. Cornwall is working hard to fix this, while keeping a commercial and tendered network in place. More to come on this topic.

Fares:

The story of fares has often got wrapped up in franchising but they are pretty separate. It’s true that Manchester has cut fares but so has the Government cut fares throughout the country. The Enhanced Partnership governance arrangements that are now common across the country allow regions to adopt consistent, low fares structures. The Enhanced Partnerships are decided by the local authority and council in partnership, so the local authority does not have direct control. But franchising isn’t the only route to low fares, if that’s what the local authority wants.

Growth:

One of the big benefits of franchising is that it gets more people onto buses. And I really hope it does. A consistent brand, a consistent marketing campaign and consistent ticketing should deliver this. It’s too early to tell if this will be true in Greater Manchester. At the moment, TfGM is reporting 5% growth on the Bee Network, which will deliver about £10 million additional revenue. This is good but not exceptional. I speak to operators around the country for my day job and many others are seeing similar levels.

What’s clear, however, is that franchising, alone, will not generate growth. The franchised London bus network is often seen as the model for franchising driving growth. And growth in London was spectacular in the 2000s. However, growth was negative in the previous decade and negative in the subsequent decade. Franchising is a great transmission network for policy: an ambitious local authority can move quickly with franchising. That’s why Ken Livingstone was able to transform the bus network in his first term. But it wasn’t just franchising: it was a huge increase in services, a dramatic expansion of bus priority, the introduction of the congestion charge and the modernisation of the bus fleet. As these policies lapsed under Boris Johnson, bus growth stalled.

Perceived Benefits of Franchising That Aren’t Really Benefits of Franchising:

Quality:

It’s often seen that franchising will drive better quality. But that’s just not true. I went to school every day in the 1990s on a bus that was old and grimy. It was operated by Leaside Buses, a franchised operator owned by the firm we would now call Arriva. But it wasn’t Arriva’s fault that my journey was miserable, nor London Transport’s: there just wasn’t enough money in the system. When the money arrived under Ken Livingstone, the system responded.

Outside London, the quality of the bus service in Birmingham in the early 2000s was poor, as National Express Group milked Travel West Midlands for profit. But Oxford and Brighton had bus networks of a far higher quality than London’s ever attained.

It is dangerous to assume that franchising is a silver bullet for quality: it’s not. Franchising puts the politicians in charge. They then need to take the decisions that drive quality.

Punctuality:

TfGM are making a lot of the fact that Bee Network buses are more reliable than buses not yet part of the Bee Network. And this makes sense: the Bee Network has lashings of political accountability whereas the legacy network is operated by commercial operators who know they will see no return for any efforts they make as their business ceases to exist by March next year. But it shouldn’t be assumed that franchising = punctuality. For a start, while the Bee Network is considerably more punctual than the legacy network, most weeks the data shows that punctuality is somewhere in the 70-79% range: i.e. one in four buses is late. If that was a rail service, no-one would be issuing press releases. The reality is that better punctuality will require big decisions on bus priority, parking, congestion charging - the policies that free up space for buses on the roads.

The contracting model doesn’t change the big things that determine whether or not buses show up on time. The New Roads and Street Works Act 1991 is still the primary driver of bus delays. In legislation heavily weighted in favour of newly-privatised utilities that the then Conservative Government wanted to make into successes, almost anyone can dig up a road for as long as they want. In Germany or France, equivalent closures face costs and penalties. Given TfGM cannot repeal the 1991 Act, what can they do? Well, they could introduce a Lane Rental scheme, as per London. TfGM is actively consulting with other local authorities to do this. It would help but it doesn’t depend on franchising to deliver.

Fundamentally, the key question is whether franchising enables the Mayor to take the tough decisions to prioritise buses. The evidence from London in the 2000s is yes, but in the 2010s is no. In Manchester, the jury is still out.

Downsides or Risks of Franchising

Political Control of Fares:

The downside to politicians having direct control and accountability is that they don’t always like doing unpopular things. Sadiq Khan, as Mayor of London, has frozen bus fares for every year of his Mayoralty, other than those in which he was directly overruled by the Government. Personally, I agree with A B B Valentine, London Transport’s Fare Officer in the 1930s, who said in his wonderful 1937 essay The Theory of Fares:

There is everything to be said for the principle that no category of traffic should regularly or indefinitely be carried at less than the direct operating costs of carrying it, although in practice even this principle may have to be ignored, for political rather than commercial reasons.

Mr Valentine goes on to qualify this heavily: transport is a natural monopoly and a public service. There are many factors that determine fares. Very little has changed since his 1937 essay was published. But I would prefer these decisions to be taken independently of day-to-day politics. And while I have sympathy with the view that fares should be held down for social reasons, I’m not a fan of using the public transport system to redistribute wealth. I’d much rather the tax credit system was used for this: it’s much better at it, and more efficient. And it means that beneficiaries can decide how to spend their extra money to best improve their own quality of life, as opposed to being told that the answer must be a bus.

Political control:

This one is the mirror image of the accountability above. Accountability is a good thing in a democracy (let’s see how much Donald Trump agrees with this statement) but politicians don’t always take decisions for the reasons professional managers would. Earlier this year, a bus route was introduced between Stamford Hill and Golders Green, two centres of the Jewish community in North London. This was a result of a direct Mayoral decision, which is his prerogative. I suspect if you’d asked TfL’s timetable planning team for a list of improvements that they could spend £3 million on, they would view this one as low down a priority list, as ranked by conventional measures of public benefit. I also suspect they would say that, despite demands for the route to exist, in practice few people will actually use it. I have no idea if the Mayor was right to demand this service, but franchising gives him the power to do so. Indeed, in some ways, politicians have more direct control over the privately-operated franchised services than the publically-owned operations in towns such as Reading and Newport. In these, there is a strict requirement for operations to be arms-length. That doesn’t apply to franchised networks.

Innovation:

Innovation is harder in the public sector. I don’t think this is a controversial statement, so I don’t think I need to spend too much time evidencing it. I’ve tried both. The public sector suffers from an understandable fear of taking a risk and the risk not paying off. Politicians don’t like to be associated with failure but risk of failure is an essential part of innovation. It’s no coincidence that one of the most innovative public sector organisations in our sector, LNER, is believed by the public to be a private business, so there’s no political accountability for any risks. Whereas political accountability is the key feature of franchising. When it comes to innovation, it’s also a bug.

Cost risk:

One of the simplest downsides to franchising is that it moves cost risk from private operators to the franchising authority. In the most recent budget, the cost of staff went up 1.2%. Previously private operators would have had no option but to bear that cost, but now it will be reflected in every tender bid TfGM receives.

Now, of course, nothing in transport is ever that simple. That’s the theory. But, of course, in practice, if the extra 1.2% made a commercial route unviable such that the operator would have withdrawn it, then the local authority would have been faced with the choice of losing the service or chipping in to tender it. But it is true that most commercial operators will run some marginally loss-making routes in order to maintain a wider network effect: these costs will be nationalised.

It also breaks the link between fuel duty and fuel duty rebate. BSOG will be paid to TfGM as opposed to the operator. This is fine if nothing changes, but creates cost risks - in either direction - if the regime changes.

Distance from customers:

One of the benefits of franchising is that it creates the potential to run the network as a holistic entity. Someone can take a helicopter view of a previously fragmented network. The danger, however, is that things are harder to see from a helicopter. I’ve seen this first-hand recently. The bus route that serves my street in Walthamstow, the W12, was recently rerouted so my street is no longer served. I’m sure there are excellent reasons why, in the round, this is the right decision. But there was almost no local communication of the decision. One of the main reasons the route served my area is a large residential care home for which this route was a lifeline. Many of the residents had no idea the change was happening.

A fragmented network has many downsides, but it often means a local, accountable manager, who knows their patch. Whereas my bus service in London is delivered by lots of contractors and departments, all operating at a London-wide scale. It can be harder to manage the local detail.

Is Franchising A good idea?

Only local areas can decide this. What only franchising can do is to make politicians feel accountable (which has pros and cons!), while keeping them away from the day-to-day operation. That’s the big benefit of franchising. By putting levers of control into one set of hands, franchising is also the most direct way to a highly consistent network.

Whether that’s worth the cost is a local decision but it’s important to be clear that these benefits come at a price.

By my estimate, in Manchester, that price is around £700 million over five years. In the context of the overall transport budget, that’s not a huge amount of money. Northern Rail receives nearly this amount every year and carries around 90 million passengers annually - just over half the number of passengers the Greater Manchester bus network carries each year. To put it another way, Northern Rail’s subsidy is around £7 per passenger (excluding Network Rail costs, which includes all the track), whereas the cost of franchising is around £1.50 per passenger. But it’s real money and local areas must know what they’re getting into.

Now, let me be clear, these costs are only my best estimate based on publicly available information. If colleagues from Greater Manchester think I’ve got bits of it wrong (and I’m certain I will have) then please do drop me a line and I’ll update with any corrections.

TfGM’s overall budgets for franchising have been exceeded for the past two years. That’s almost certainly a result of the increase in the industry’s cost base. But franchising means those costs sit with the local authority and must sit with the local authority. Franchising is not risk-free.

But is it a good idea?

I don’t think there’s a clear answer to that. Franchising puts elected politicians in charge. Politicians are accountable to their voters. That’s us.

So my best suggestion is to look at your neighbours and form a view as to whether you think they’ll vote for a politician who’ll deliver better bus services.

Then make your decision.

———-

In future posts, we’ll look at some of the work being done in Cornwall, Derbyshire and Norfolk with Bus Service Improvement Plan (BSIP) funding.

———-

What do you think of this? Tell me on LinkedIn

👋 I'm 𝗧𝗵𝗼𝗺𝗮𝘀. I help organisations like yours drive 𝗶𝗻𝗻𝗼𝘃𝗮𝘁𝗶𝗼𝗻, deliver 𝗰𝗵𝗮𝗻𝗴𝗲, and achieve 𝗳𝗮𝘀𝘁𝗲𝗿 results, drawing on 20 years of leadership across public and private sectors.

🚀 I offer 𝘀𝗽𝗲𝗮𝗸𝗶𝗻𝗴, 𝗺𝗲𝗻𝘁𝗼𝗿𝗶𝗻𝗴, and 𝗰𝗼𝗻𝘀𝘂𝗹𝘁𝗶𝗻𝗴 that energise teams, shape strategies and remove barriers to change. Whether you aim to accelerate innovation, drive change, or inspire your people, I’m here to help. Let’s talk!