Has London given up on Buses?

LONDON BUSES USED TO LEAD THE WORLD. BUT HAS IT NOW FALLEN BEHIND?

Going nowhere fast

I don’t use buses as much as I used to.

I don’t mean because of Covid - I mean anytime in the last five years.

I’ve put this down to lots of things: my youngest got travel sick on buses a few times, we no longer make regular trips to the Museum of Childhood (bus 48 from our house) and life with two kids doesn’t leave as much free time for bus-based days out.

But maybe it’s also because, imperceptibly, buses have got worse.

Indeed, when you step back and look at London’s buses, you don’t get a sense of dynamism and innovation.

Bus priority

Let’s look at the most important thing: bus priority. The key strategic rationale for the creation of TfL was one organisation to control all modes of transport, including strategic roads. And, at first, it really seemed to work. From their inception in 1968, bus lanes grew by an average of 5 miles a year, peaking at 175 miles in 2006 after a surge in the first five years of the century under TfL.

Since then, bus lane mileage has largely stagnated and may even have declined (I can’t tell for certain as the TfL bus lanes database is not available to the public - why not?). But my local main road (Lea Bridge Road in Walthamstow) has seen its length of bus lane drastically reduced to create space for a cycle superhighway, on a project lead by the local authority but funded by TfL.

I used to be a bus lane

Given increasing traffic, it is unsurprising that stagnating (or reducing) bus priority has caused a collapse in bus speeds: in 2002, the average speed of AM peak buses in Central London was 10.9 mph, rising to 14 mph for inner London radials and 15.7 mph for outer London buses. By 2019/20, the average AM peak bus speed was just 8.4mph.

As a user, it certainly feels so. The result, of course, is lower frequencies and less reliability.

Slower buses has caused a need to consolidate resources. Indeed, I no longer could use the 48 to take my daughter to the Museum of Childhood, as it was withdrawn in 2019.

And, as a result, it’s hardly that surprising that passenger satisfaction has fallen to just 85%, lower than virtually anywhere in England other than Milton Keynes. The lowest measures are for reliability and value for money: both at 81%. These are probably connected.

And, of course, these are the passengers still using the bus in London; but some no longer are. From a peak of 2.4 billion in 2013/4, bus use in London fell to 2.1 billion in 2019/20.

Not smiling now

Undoubtedly falling bus speeds driven by increased congestion not being matched by improved bus priority is the primary reason for the trend above.

But there may be others.

Let’s go through some of the key elements of a bus journey:

Bus stops

At the most basic level, the bus stop is probably the most important feature of a bus journey for a passenger. Without a bus stop, it’s impossible to start. Back in the early noughties, TfL was leading the way. The new bus stop flag design, created by Fitch in 1991, was being rolled out across London.

I remember the bus stop team at National Express’s West Midlands bus division proudly showing off their new London-inspired flag design when I was a graduate trainee in 2002. Around the same time, a standardised bus stop design was created to replace the mess of shelters that had previously existed; and this design became universal throughout London in the early part of the century.

The London bus stop. Standardised but not special.

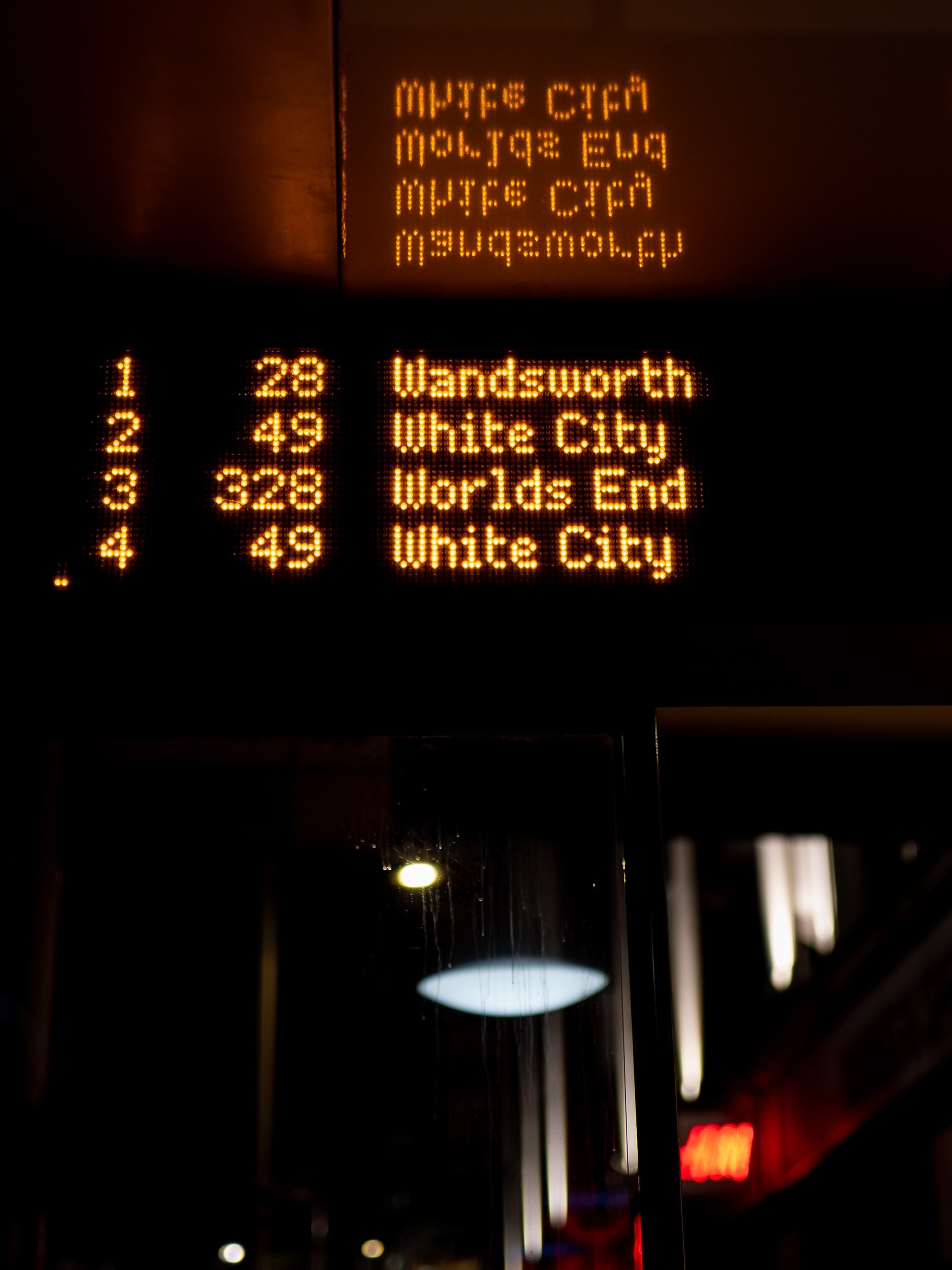

Also in the early 2000s, new iBus technology was introduced, resulting in ‘countdown’ screens, giving bus users access to live departure times for the first time. A target was set to roll out 2,500 of these screens; a target that was achieved in 2012. Since then, almost no additional screens have been deployed, with 2,584 out there in 2019.

10 years ago, this was the future

Finally, TfL led the way in the provision of open data. In 2009, TfL created a dedicated developers’ area on its website. By 2012, they had 4,000 developers registered on the platform, accessing data feeds including bus arrivals. This led directly to the creation of apps such as Citymapper and inspired startups still operating in the transport space such as UrbanThings; which started out as a bus checking app. Bus open data from TfL has finally inspired a similar project from DfT, which saw a key moment last month. However, as with so many things, TfL’s open data prime is in the past. A developer can access bus arrivals but not what facilities are available, how crowded the bus is or how the network is used. Or, indeed, where the bus lanes are...

Live bus times on your phone! 10 years ago, it felt like magic

In summary, about 8 years ago, the TfL bus stop experience reached its peak. A simple, easy to understand set of printed info, a decently comfortable (though not great) standardised shelter, a growing network of screens telling you when the bus was coming and the ability to download an app giving live bus times.

Since then, bluntly, nothing has changed. It may be no coincidence that 8 years is also the time since the peak in London bus useage.

The bus

This is an area that has seen a lot of change in recent years, but not always entirely for the right reasons.

Genuinely beautiful - on an empty road…

The “New Routemaster” is the single biggest bus investment in the UK of recent years. But it was a political project. The purpose was to enable an open-platform, conductor-operated bus so that Boris Johnson could deliver on an election promise, despite that promise being both impractical and costly. The bus achieved that purpose for a few months, but the conductors have vanished, the benefits of three-door boarding have been lost and what you’re left with is a design icon. I love the look of the New Routemaster: it’s beautiful. But it’s designed to be seen as opposed to ridden-in. The windows are tiny and they don’t have charging points, despite these now being common outside London.

That’s not to say there hasn’t been progress: I live close to route 69, which saw one of the very first wireless charged electric buses in the world. Overall, huge progress has been made on decarbonisation (with TfL acting as a global leader in the field of hydrogen) - but not in a way that impacts ridership. Indeed, one of the things that has surprised me is how little TfL seems to want to sell the idea that buses are green. Operators in other parts of the country have really harnessed the sense of progress of electric buses but an electric bus in London looks very much like a diesel bus, which seems like a wasted opportunity.

A red bus that’s proud to be green

Paying

It’s such a familiar story. TfL led the world when it came to the introduction of contactless in 2012. For a while, in the early years, TfL was the largest contactless merchant in Europe. Very possibly, the extraordinary convenience of being able to touch a debit card and pay for a bus ride was one of the reasons why usage rose into 2013 even despite increased congestion and the stagnation of bus priority.

But contactless is now commonplace and we’re nearly 10 years on. What is the next innovation in the pipeline? There’s no sign of it.

Now, you could argue that contactless is perfect and there’s no need of anything new. But even within contactless, change could have been possible.

For example, TfL still maintains an entirely separate pricing structure for bus and tube. This feels like a real missed opportunity given that one of the key purposes of an integrated network is for… an integrated network.

I suspect the reason is that the old Oyster card has not, as was originally intended when contactless was introduced, been retired and is only capable of much less flexible pricing structures than the contactless back office. But the result is that a two-leg tube+tube journey (or train+tube, for that matter) will be counted as one single ride, whereas a two-leg tube+bus ride incurs two entirely separate fares. This massively disincentivises use of bus as a feeder to other networks. If you’re going to be charged £3 (2 x £1.50) to get the bus to the station and home in the evening, you are much more likely to drive and pay the parking fee.

Promotion

OK, I stray into dangerous and subjective territory here. Everyone’s an expert on marketing, even without evidence. Please forgive me. But one of the real differences between buses in cities outside London that do buses well is that they use the buses to promote their services. I don’t know of any empirical evidence that this works (but if you do, I’d love to hear about it) but if you look down the list of cities where bus use has grown (or where bus mode share is traditionally high), you see cities that do very clear route branding on buses. James Freeman describes why this is a good idea on The Freewheeling Podcast, and it’s worth a listen. It makes intuitive sense: a car-user is much more likely to try the bus if they know where it goes, and they can find that out without even trying just by seeing a bus pass them in the street.

A route that knows where it’s going

In the early 2000s, TfL route-branded central London Routemaster routes but the practice was abandoned with the vehicles.

Bus route branding on the 38 (the heart in the centre of the logo became somewhat iconic)

In 2017, a return to this approach was announced but it was half-hearted and never consistently implemented. I know as one of the trial routes passes near my house. Four years on, little appears to have happened to learn from it or expand it. Trent Barton, Transdev, Reading Buses or Brighton & Hove have a lot to teach in this area.

Detail

My final piece of evidence is a seeming reluctance to nab best practice when it exists elsewhere. My work with Snap has taken me to Nottingham a lot in the last few years; a city I barely knew previously. Travelling on both Trent Barton and NCT routes, I’ve been impressed by the friendliness, cleanliness, design-consciousness and… well, just quality.

One thing I really liked from Trent Barton was named route managers on buses. I can see that this is something hard to replicate in the London model (would they be from the contracted operator or central TfL?) but the prevalence of phone charging - even three years ago - absolutely could have been (to be fair, London does finally have a few buses with sockets, but it’s taken a while).

And what about this glorious invention from Go North East? That horrid seat at the back of the bus that always has to face backwards because of the wheel arch? Turn it into a footrest and instantly something that suggests you don’t care about customer comfort becomes something that proves you do. And if a family of four want to sit together, you can fold the seat down.

Please DO put your feet on the seats

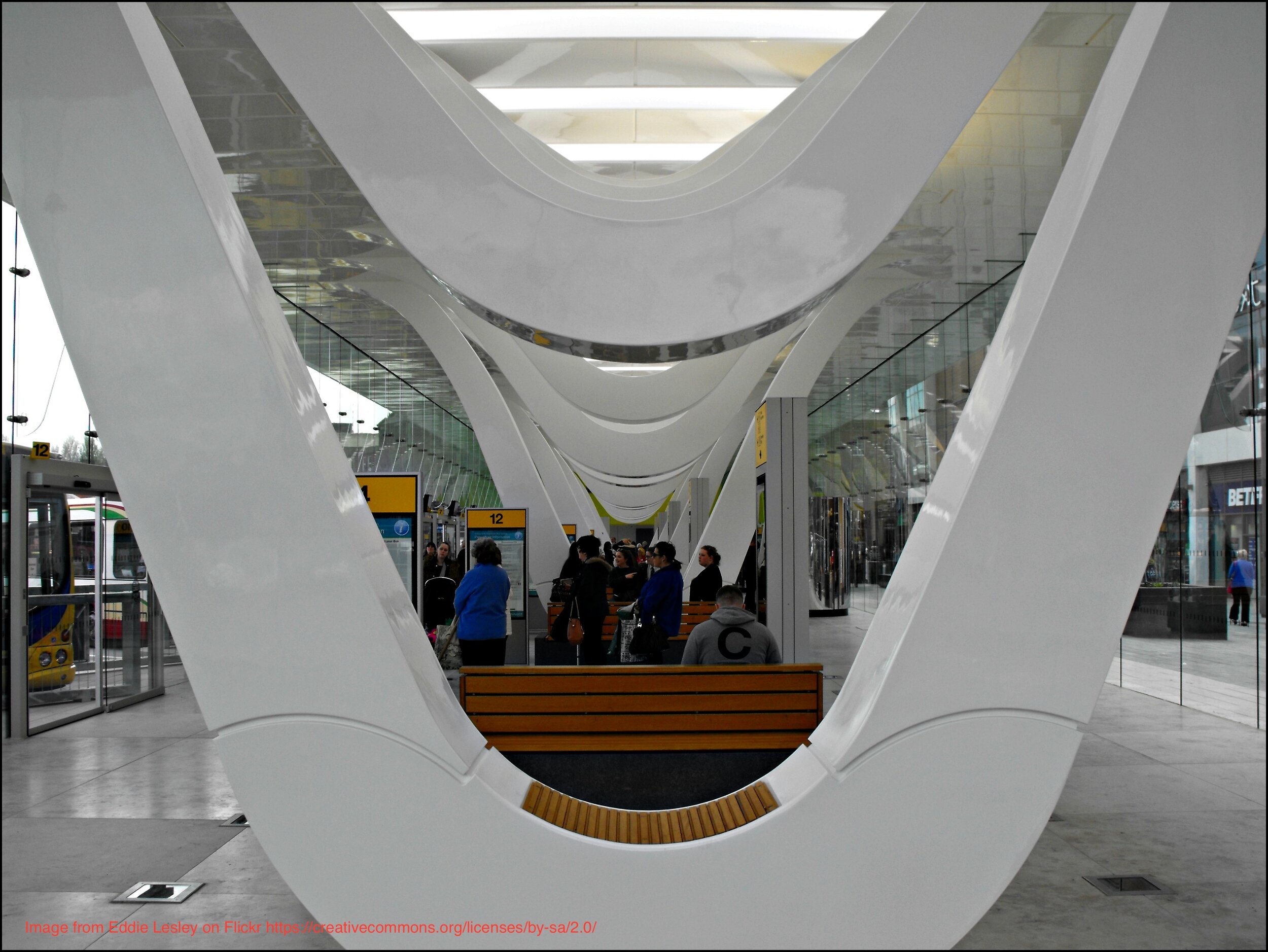

My local bus station, Walthamstow Central, was state-of-the-art when it opened in 2005. But it is now windswept and miserable. The only departure screen is located at the entrance, meaning that you can see either the buses or the screen but never both at the same time. Now there is no shortage of terrible bus stations outside London but it is notable that the best bus stations are now elsewhere. Compare Walthamstow Central with the wonder that is Blackburn bus station, which opened in 2016.

Another Lancashire town, Burnley, is served by the Witchway bus from Transdev. It has some incredible customer-centric features. I love, for example, the libraries on board (also found on some other Transdev routes) that lean into the recent global trend for little free libraries.

This little library moves

Obviously, these buses are expensive and wouldn’t be suitable for all routes. But that is true of the New Routemaster. But for a route like, for example, the hour-long slog round the North Circular on the 34 from Walthamstow Central to New Barnet, you can imagine more suburbanite drivers being willing to swap from their car for a seat like this:

Unfortunately, London gives off a slight sense of complacency at the moment. Buses that don’t promote where they go, aren’t particularly designed around customers and which get slower by the year.

The worry is that this was good enough for gentle decline before Covid but will not be enough for recovery afterwards.

Now, this sounds like a criticism of London Buses. But it isn’t really. At least, not of London Buses as an organisation. The fact is that TfL is a political organisation and dependent on leadership for progress.

A lot has been made of the much-vaunted success of “the TfL model”. But perhaps it’s not the “TfL model” that made London buses a success in the early noughties: it was leadership. London was lucky with its first Mayor, and because TfL was newly created at the time, this luck rubbed off onto TfL. Ken Livingstone was a radical Marxist who, unable to achieve radical change in the global economy, focused instead on radical change in the world of buses. Double win!

As I discussed when talking about the National Bus Strategy, the early years of TfL saw the combination of massive bus priority and the introduction of the congestion charge. This combination was the key driver of the growth of the early 2000s, and that kind of leadership has not occurred since.

But he was replaced by Boris Johnson, who focused on expensive vanity projects (cable car, New Routemaster, garden bridge, Boris Island) and, otherwise, cut ribbons on projects initiated by his predecessor (bike hire, Overground extension) with no vision of his own. He also managed the extraordinary ‘achievement’ of negotiating away TfL’s Government grant, walking away with less than the Treasury intended as its lowest offer.

Boris Johnson: impractical, expensive and a lack of attention to detail. I know, hard to believe.

So what does all this tell us? Well, another of my guests on The Freewheeling Podcast, River Tamoor Baig, has a clear view on one of the big barriers to progress in transport:

Rail and bus can work either nationalised or privatised. We just need to pick one and let it thrive. What we’ve got right now is this kind of whipping effect where we look to the left, we look to the right and we don’t really get anywhere as a result because we’re constantly changing the structure.

Instead of focusing on structure, perhaps we need to focus on leadership. If Alex Hornby, Ian Morgan or James Freeman were Mayor of London (I realise this is quite a stretch of the imagination in some cases!), then buses would again have a senior champion obsessed with connecting them with the customer. And had Ken Livingstone been CEO of Transdev…. OK, that really is a stretch too far! But you get the point! :-)

The next Mayor of London?