What I want for my Birthday

This isn’t my house. We’d have more beer and no baileys.

I turn 40 today!

Given that male life expectancy is 80, that means I’m pretty much exactly half-way through.

So now feels like a good time to look back at what has changed in the 40 years I’ve been alive; and think about what I’d like to happen in the 40 years still to come.

What’s changed

In many respects, the world we live in feels a much better one than the world I was born into.

Back in 1981, car was unquestionably dominant, and the only question for Government was how quickly it could stop paying for public transport.

The Shapps-Williams equivalent of my babyhood was the Serpell Report. Written in 1982, it presented options for how to cut the cost of running the railway. From the perspective of 2021, it’s staggering that Option A was a serious proposal from a Government report. It shows a proposed network that consists of the West Coast main line, parts of the East Coast and Great Western main lines and some main lines in South East England. And that is it.

How incredible that, in my lifetime, it was seriously proposed that the entire rail service would be withdrawn in cities like Nottingham, Sheffield, Leicester, Oxford, Cambridge and Plymouth. Levelling up it wasn’t! Northern England, Wales and Scotland would have lost their entire rail networks (other than the intercity lines to London) (though, remarkably, Eastbourne somehow survived):

In some ways, the radicalism of Option A was helpful. Even though the report also offered Option B, Option C (divided into Option C1, Option C2, Option C3) and Option D; all with differing levels of cuts, it was Option A that was the big news story. (The report briefly considered Option H - the “High investment option” - but quickly ruled out the possibility of improving the railways as a solution).

The Serpell Report ended up quietly shelved by the Government and 1982 ended up as the low point in rail usage.

Meanwhile, the solution to cutting the cost of bus services was deregulation: taking the state out of bus provision entirely. Unlike the Serpell Report, this didn’t come with a politically explosive map showing vast cuts in established bus routes. But the cuts came, as the new system was used as an opportunity to reduce funding.

But the tide was starting to turn. 1986 saw the opening of the final section of the M25; the last major motorway to be built in the UK. In the 1990s, the Government tried to adopt the same-old approach of building more and wider roads (and ignoring investment in public transport) but the public mood was starting to change.

Aged 15, I remember catching the train out to Newbury to protest against the A34 Newbury by-pass. Similar protests took place at Twyford Down for the M3 extension and in Leytonstone, East London (just round the corner from where I now live) against the M11 link road. All these roads were built but the Government was alerted to the fact that ploughing motorways through natural landscapes or peoples’ homes came with a political cost that hadn’t existed a few years’ earlier.

The 1990s also saw the first evidence that investing in public transport worked. Chiltern Railways, as a private sector company, continued the work started by British Rail in growing a railway that had previously been slated for closure. With the first post-privatisation new train order, reopened tracks and brand new stations, Chiltern Railways cruelly exposed the flawed thinking of the Serpell Report. That line is now profitable.

And then, in the 2000s, Ken Livingstone demonstrated what was really possible. The combination of the congestion charge, the Oyster card and a major expansion of bus priority turned London into a global transport leader. It happened so fast! I used to commute to school by bus in the late 1990s and it was slow, grimy and unpleasant. Ken’s was a very simple formula; it was popular and Ken Livingstone won re-election after he did it. Yet, for some reason, it’s never been replicated.

Today, the position is unrecognisable from when I was born. Politicians publicly support public transport and Government strategies fall over themselves to show how much better they want it to become. It is official Government policy to redistribute road space from cars to bikes and buses. Few people seriously think that more roads are the answer.

Interestingly, technological change has not made a significant impact on transport and mobility in my first 40 years. The vast majority of tech interventions have been improvements in bookings and payments, as opposed to the journey themselves. (I realise I’m very much saying this from the perspective of someone that travels in the vehicles. My engineering colleagues tell me that quite a lot has changed underneath! But while the physical trains and buses have changed quite a bit, the core operating models feel very similar). The biggest tech development has been Uber, but this is only a better way of booking minicabs (which, themselves, haven’t changed that much).

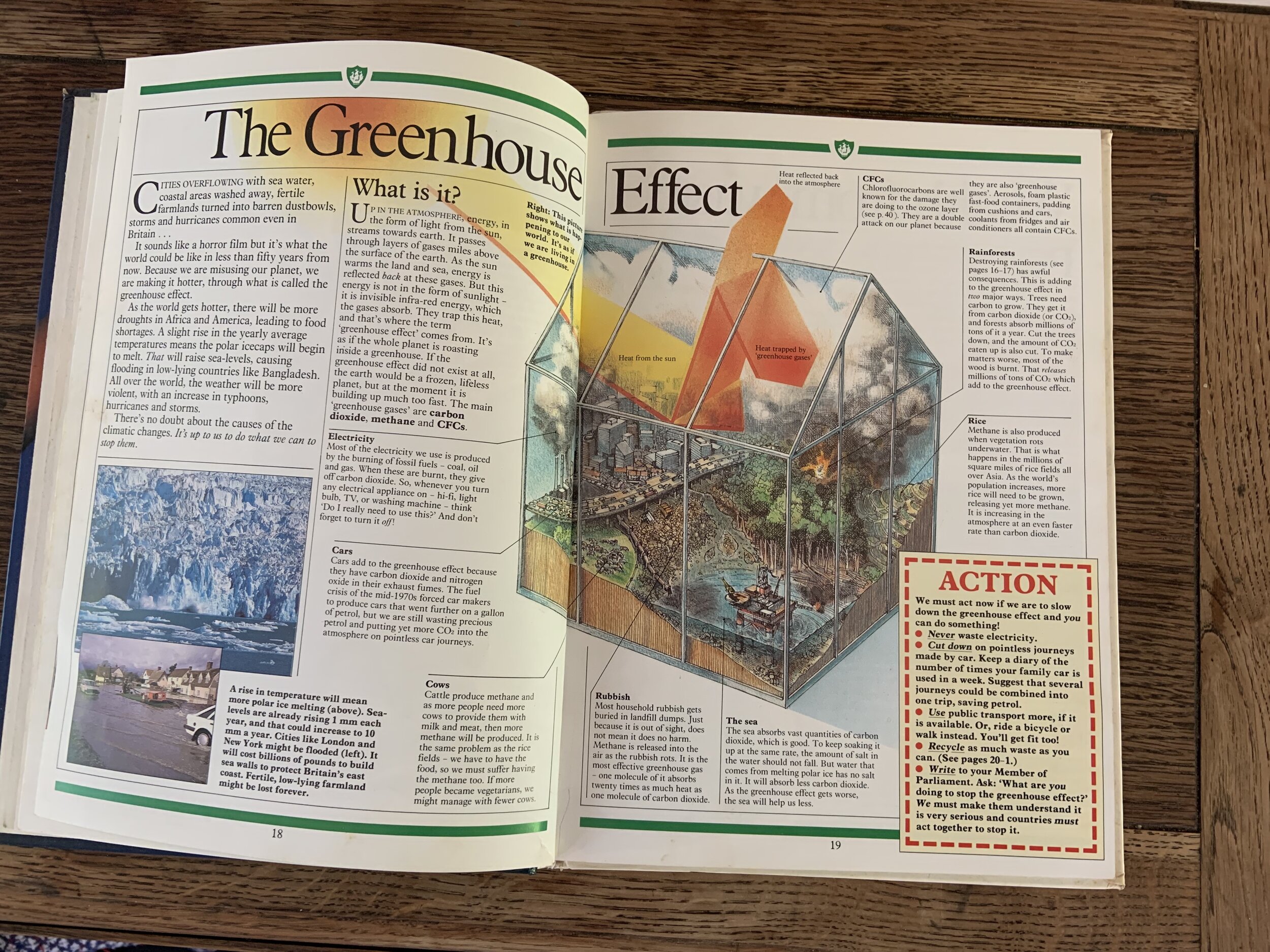

And, of course, there is climate change. I still have my childhood copy of The Blue Peter Green Book. It was quite explicit about the dangers of climate change (it was called “The Greenhouse Effect” then, remember?). No-one can see we didn’t know in the 1980s.

But we certainly didn’t act like we knew. Possibly the most significant pivot point in my lifetime was when the US Supreme Court decided that - despite winning fewer votes - George W Bush had won the Presidential election. Instead of a man who went on to become the world’s leading climate change campaigner (before being supplanted by Greta Thunberg), the US President was a climate-change denier who undermined climate science at every opportunity.

As a result, the first 40 years of my life have seen a near-constant increase in carbon emissions. Reductions have been largely accidental: the financial crisis or Covid, not deliberate policy. Britain has been a world-leader in climate reduction but that was because of the reduction in subsidy to heavy industry. The emissions are still made; they’re just made in China.

What comes next?

It’s obviously impossible to predict what the world will look like in 2061. Anyone who tried to predict 2021 in 1981 would have failed miserably, on almost every count. Indeed, given that the Serpell Report had just been commissioned but not yet published (and therefore there’d been no backlash), they would probably have assumed that the road network would continue to expand and the rail network to decline. Pivot points can occur at any time and without warning.

And that is, in fact, a warning in itself. Right now, the environment seems set fair for public transport but the environment can change. Elon Musk is leading a revolution in automotive entirely predicated on the idea that cars are the solution and that public transport should simply mean cars in tunnels. The developing world is building roads and buying cars. Anyone foreecasting the next forty years based on recent trends would forecast faster growth in car use than public transport use. If a different future is going to be created, it will have to be based on results. Decisions will be made on the basis of whether public transport continue to improve.

In that context, technological change does feel like it might have more of an impact in the next 40 years than the last 40. I do think flying taxis will happen and they will be a niche product for affluent commuters, but I don’t think they’ll be a significant part of the future. But ground-level automation will be. Autonomous buses will create the potential to expand service provision without expanding costs; perhaps to a dramatic degree. Meanwhile, autonomous delivery robots will turn home delivery of groceries from more expensive than supermarket shopping to the cheaper and more convenient norm - further facilitating car-free living. Despite the fact that the hype is around cars, I suspect we’ll have far more non-car automotive use-cases as buses and delivery pods are easier and safer to automate than cars.

The Achilles heel of public transport has always been that it requires population density. But micromobility (if intelligently integrated into mainstream networks) solve that problem. E-scooters pose risks (both safety and to the viability of transport networks) but they also create the potential for public transport to have the capillary connections to trunk networks that, previously, have been the preserve of cars.

Public transport will also catch up with e-commerce and finally put customers in charge through the magic of star ratings. At some point between now and 2061, I can visualise every customer having a constant digital companion, feeding them the latest information and receiving dynamic feedback which can then act as an automatic input into the system so that issues can be resolved in real time. This matters because if public transport is better, more people will use it.

And as more people use it, streets will be repurposed for it, and cityscapes will become greener and healthier. As people discover how much they prefer these cityscapes, they will vote for politicians who prioritise public transport further and the virtuous circle will continue.

By 2061, the world will look as different from today as today’s world looks from 1981. Clean, green, healthy streets are almost within reach.

I joined the world of public transport because I believe in human connections. The pandemic has been hard on those of us who get our kicks out of enabling people to get together for work, business, leisure and pleasure. One of my key goals of the carbon transition is that we can enable anyone to get anywhere but without the detrimental impact on both the environment and the streetscape that we’ve seen in the past.

To make this happen we need a thriving public transport industry. The first thing you see when you come into my house is my all-time favourite poster. It’s this magical McDonald Gill (younger brother of Eric Gill, of Gill Sans fame) masterpiece. It shows a rich, dense London streetscape, filled with wit and humour. The sense is of bustle and connections and life. And around the edge is the caption:

BY PAYING US YOUR PENNIES YOU GO ABOUT YOUR BUSINESS IN TRAMS, ELECTRIC TRAINS AND MOTOR DRIVEN BUSES IN THIS LARGEST OF ALL CITIES, GREAT LONDON BY THE THAMES

For me, that caption has it all. The sense of the importance of public transport and the sense of stability and reliability when it’s paid for not through endless bailouts but because people want it and use it. I would love it if, by 2061, the virtuous circle I described above could have spun enough times to make outstanding transport and mobility (combined!) as much a stable, commercial bedrock of modern life as it was in 1914 and as, for example, the food industry is today.

McDonald Gill’s masterpiece on the wall of my hall at home

But, of course, there is also the possibility that a backlash will occur and we’ll revert to filling the streets up with cars. Because they’re electric, we’ll think we’ve addressed climate change (when we haven’t) and we’ll believe that new technology will solve congestion (it won’t).

I believe the first of these futures is possible but it is certainly not guaranteed. It will be up to all of us who thinks this is the right future to work to make it happen.

In terms of a birthday present, the gift I’m after is road pricing. It’s essential and as soon as it’s bedded in, will become utterly normal. Remember the fury about Sunday trading? No, but it happened. Or how controversial gay marriage was? But now it’s established fact. Road pricing will be politically toxic until suddenly it’s just how things are. But it’s the critical enabler to the future I describe so we need to get on with it.

I’ll be having today off and (probably!) won’t be thinking too much about either the past or future of transport and mobility.

But I’ll be back tomorrow to start another decade doing my tiny bit (as part of a team of the tens of thousands of us who work in transport and mobility) to help create a future in which everyone stays connected to everyone else, but cleanly, greenly and safely.