£1bn says flying taxis are the future

Amara’s Law states “We tend to overestimate the effect of a technology in the short run and underestimate the effect in the long run.”

So in that context, let’s attempt to think through the likely impact of flying taxis.

Last month, the German flying taxi startup Lilium landed on the stock exchange valued at €3.3bn. Startups creating new eVTOL vehicles (as they are more properly known: electric Vertical Take-Off and Landing vehicles) raised $1.3bn investment last year; 80% up on the year before.

A lot of big bets are being made that flying taxis are the future.

Is it a bird? Is it a plane?

The eVTOL label actually disguises various different markets for flying taxis. Volocopter has raised more than €300m. Their pitch is that

“the inner-city air taxi mission represents the highest demand and thus business potential”

The Volocopter looks like a teeny, tiny quiet helicopter. They envisage little helipads (obviously called Volopads) on the sides of buildings, with Volcopters being summoned by app to take people between hotel and shopping centre or between hotel and airport. They’ll do trips of up to 30-35km and they’ll fly at 80-100 km/h. There are two seats: initially, one will be one for the pilot and one for the passenger. Eventually, they envisage the Volocopter flying autonomously, which will provide 2 passenger seats.

Volocopter: just you, your pilot and the open skies

Being teeny-tiny and with a small range, the Volocopter is very energy efficient. They boast that it will do an entire 30km ‘mission’ on 50kwh; the same charge as a full Tesla. Having said that, of course, efficiency is relative - and I suspect a Tesla owner would be thoroughly fed up if their new car only did 30km per charge. Moreover, that means that a Volocopter will use almost exactly the same amount of electricity per mile as an electric bus; but carry around 1/60th of the people. Even teeny-tiny flying taxis are still going to require a lot of juice!

Joby Aviation doesn’t believe that flying taxis need to be quite so teeny-tiny. They are building something that looks like a big drone, with five seats (four for passengers). The range is 150 miles and the top speed 200mph, so much more equivalent to the existing helicopter product.

Joby Aviation: seats for the whole family

Like Volocopter, they see their mission as being to provide better intracity transport. They have also just hit the stock market, this time with a valuation of $6.6bn.

Joby believe that each megadrone will cost $1.3 million to manufacture and generate $2.2 million in annual revenue, resulting in a payback period of 1.3 years per plane based on an assumed passenger load factor of 2.3 and approximately 4,500 operating hours per year. That assumed load factor of 2.3 is notable as Volocopter assert that 1 passenger seat is sufficient as the average unconstrained demand would be 1.3 passengers per trip. At these numbers, who’s right about that extra passenger will make a big difference!

Volocopter are critical of the Joby model, asserting that the extra range and speed will make their vehicles too noisy to work in city centres and the batteries too heavy to be fuel-efficient. Joby insist that their plane will have the equivalent fuel consumption to an electric car. Really?! It turns out this is because they assume the equivalent ground-based vehicle will have an average occupancy of 1.1, but their elevated one will have an average occupancy of 2.5. The discrepancy is not fully explained.

Joby claim that the operating cost of the vehicle will be $95 per 25 mile trip; so about $4 per mile. McKinsey believes that the true cost could end up at half that point, once the whole ecosystem is up and running. Joby have three European target markets; of which one is London.

Closer to home are Vertical Aerospace; based in Bristol. As is typical for British startups, they’ve a lot less money than their American or German counterparts. £2.3m of Government money found its way to them last year, with their plane looking much more like Joby’s. Also flying at 200mph, it has a range of 120 miles. They envisage it being used to cut the journey time from Heathrow to Canary Wharf from its current 1hr 22 to just 13 mins. Of course, Crossrail will get it down to 50 minutes; though at Crossrail’s current rate of progress, it’s possible that the flying taxis will get there first…

Is it a plane, is it a helicopter; no, it’s Vertical Aerospace

And then, of course, there’s Lilium; the ones who hit it big on the stock market last month. They are focused on a slightly longer trip; what they call “Regional Air Mobility”. They use Switzerland to illustrate the opportunity: they believe that they can offer journey times between Swiss towns at a fraction of the existing rail times, but at the cost of a first class rail fare

Lilium journey time forecasts for Switzerland

Stations

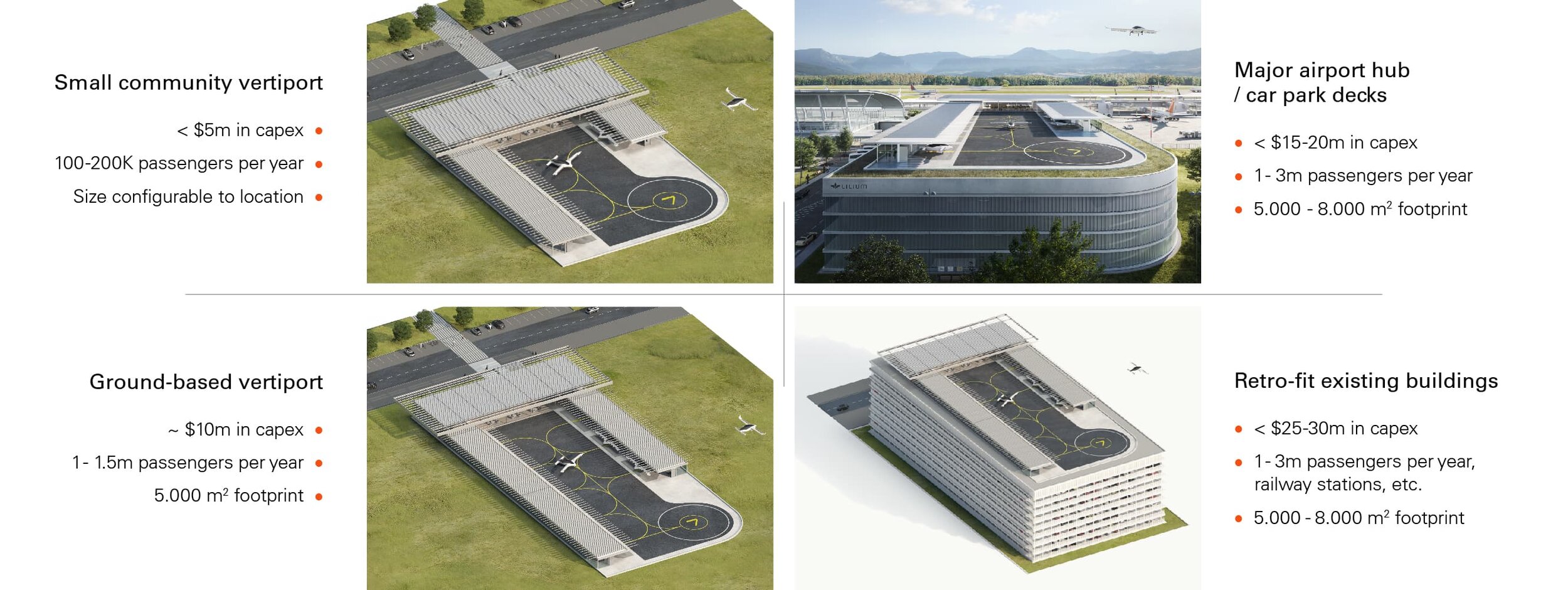

Lilium, with their regional travel model, say that “we could effectively service the entire downtown area using just one or two pads”. They also estimate the cost of Vertiports:

It’s worth noting that a 5,000 square metre vertiport will, according to their estimates, move around 1m passengers per year with the largest 8,000 square metre vertiport moving 3m passengers. Even ignoring the likelihood of optimism bias in these estimates, it’s worth noting that this is about 1/6th the area of, for example, Liverpool Street station but 1/22th of passenger numbers. Even in the most optimistic case, flying taxis aren’t space-efficient.

Here’s Lilium’s walk-through of a vertiport:

Lilium seem to view the vertiports as something like a cross between a station and an airport.

But, of course, one or two vertiports per downtown doesn’t work if the main mission is to connect different bits of the city together. McKinsey, when looking at the more ‘traditional’ intra-urban flying taxi concept, reckon each city will need a similar number of ‘vertiports’ as there are tube stations; very roughly. They estimate that a city the size of London could have around 100, based around a network of big ‘vertihubs’, medium ‘vertibases’ and small ‘vertipads.’ They believe the entire city-wide network could be built out for less than $45m, which seems crazy low to me.

McKinsey’s estimate of the costs of Vertistuff per city

To pilot or not to pilot

Most of the flying taxi firms envisaging starting with pilots and then moving to full autonomy. This creates a real economic challenge as on a vehicle with either one or two fare-paying passengers, the pilot is a significant proportion of the cost. McKinsey estimate that a pilot on board will double the operating cost.

Even with pilots, an entirely new air traffic control solution needs to be invented. Dubbed UTM (Unmanned Traffic Management), this is the automated system that will direct flying taxis around the ‘roads’ in the sky - often at pretty tight frequencies.

Who runs this system and how the various operators integrate into it (especially if different operating regions overlap) seems to be an unanswered question at the moment

Lots to think about

Indeed, there are lots of unanswered questions. Some are commercial: the various operators all calculate their low fare assumptions based on very high levels of utilisation. But will that actually happen? Peakiness is the bane of so many transport modes and the flying taxi model either looks like Uber (which only works because, off-peak, drivers are willing to leave their app running while they go about their business; thus achieving high availability with low utilisation) or a more conventional set of regional bus routes (which work by achieving high load factors in the peak to compensate for the off-peak). Neither of these will be possible in the flying taxi market - at least, not if the goal is to make it a mass-market proposition off the back of low fares.

Then there are operational and technical questions. No-one wants to talk about bird-strikes and no-one wants to ask whether consumers will actually be willing to adopt it. The railway adopts a principle that risk should be managed to be ALARP (“As Low As Reasonably Practicable”). Some people might argue that the best way to achieve this is not to fill the sky with these things at all.

The carbon implication is also pretty terrifying. The manufacturers put a lot of effort into highlighting their equivalence with electric cars. But it’s nonsense: based on our current grid, they will instantly become the highest carbon footprint mode of e-travel; and one of the highest carbon footprint modes of travel. We will need a very high capacity and very green grid to avoid them becoming a carbon catastrophe in their own right. Because, remember, the capacity of the renewable grid will need to be high enough to feed all our demand for flying taxis and service consumers and businesses on the ground. It’s no use eVTOL companies boasting of their green credentials if they’ve hoovered up all the renewable electricity, such that factories and houses have to rely on fossil fuels.

And then there is noise. It feels like there’s a real assumption being made throughout all of these firms’ materials that because they’re electric, they are quiet. And, of course, they will be a lot quieter. But a lot of vehicle noise is not caused by the engine but by air turbulence. Imagine standing on a station platform next to both an electric train and a diesel train: when they start rolling, there’s no doubt that the electric train is immeasurably quieter. But if you were standing at a station and both of them passed through non-stop at 100mph, then the diesel train might be noisier but the electric train is still pretty damned noisy. Given these vehicles all move at speeds equivalent to fast trains (and will be powered at take-off by either rotors or jet engines), it remains to be seen just how quiet they are in reality.

SOCIAL GOOD?

Unsurprisingly, the various startups put a lot of effort into talking up the social good of their products. However, while they all use various numerical gymnastics with utilisation and load factors to show how affordable they’ll be, the reality is that this is a product for rich people. Some of the operators pitch flying taxis as a solution to congestion. That needs quashing straight away. It’s a perfectly reasonable thing to decide that flying taxis are a great thing for the world, but there is no possibility of them helping with traffic. Flying taxis are so transformational in their potential that they will generate new demand; they won’t replace car journeys. And, even if they did, as we already know, if nothing else changes on the ground, the tiny amounts of roadspace released by someone hiring a flying taxi instead of an Uber will instantly be consumed by another car. That’s how traffic works.

I have no doubt that in the coming years, flying taxi firms will be sniffing at the public purse, seeking support for new Vertiports, control systems and all the various other bits of infrastructure necessary to make the market work. But a market for rich folk to get places faster in a carbon-intensive way needs to be entirely private; and regulated to ensure that its effects on others (primarily noise) are limited in the extreme. Otherwise just at the moment that we finally lose noisy cars from our cities, we will replace them with noisy drones in our skies.

What does the future hold?

As per Amara’s law, the short-term future for flying taxis is probably less exciting that their promoters promise. All of the operators are promising launches in 2023 or 2024. Joby, for example, aims to deploy more than 10,000 aircraft in the coming decade, with just under 1,000 in service by 2026. Well, maybe. But there’s a lot to solve by then - and that doesn’t mean the plane technology; it means everything around the edges from control systems to bird strikes to somewhere to land.

But also as per Amara’s law, the long-term future is more significant than we can currently imagine. The good news about all this taking some time is that I can make a prediction (or, indeed, several predictions) safe in the knowledge that no-one will remember and check if I was right.

Mystic Ableman

My first prediction is that the Volocopter vision of flying taxis batting around the city from vertiports spaced like tube stations will not happen. The most resource-intensive part of the journey is take-off. Take-off uses most electricity, generates most noise and consumes most space. So it makes sense that the model that finally emerges will maximise time in the air and minimise time taking off. The urban flying taxi model does the opposite. Moreover, the urban flying taxi concept will require most public support - in the form of space allocated to vertiports and loose noise regulations. But any kind of public sector support to this product will be seen as subsidising a plaything for the wealthy elite and that will not be politically acceptable if there are any kind of meaningful externalities.

However, the Lilium vision of regional connectivity feels more achievable and more transformational. Volocopter promise high speed nips around cities, but we should (should!!) be able to achieve these on the ground if we finally start using roadspace efficiently. Queuing up for a baby helicopter to take me to Canary Wharf may not save me much time compared to simply getting Crossrail, or an e-scooter or even a bus - if we could clear the traffic out of the way.

And, anyway, while I struggle to envisage veloports all round town, it seems perfectly reasonable to envisage some - with flight routes carefully designed to minimise sound and visual impact (a bit like London’s existing heliport, from where helicopters are required to fly out along the Thames). Interestingly, the places where the regional connectivity solution seems most applicable are muli-polar urban areas with comparatively lower population densities. One of Lilium’s first launches is intended to be North-Rhine Westphalia, and as I’ve said before, the North of England urban city belt has a lot in common with North-Rhine Westphalia. Even with HS3, journeys like Rochdale to Barnsley are going to be really hard to connect up. Rochdale to Barnsley are 30 miles apart but the public transport journey takes two hours. Faster trains on the Manchester <> Leeds HS3 route will make only marginal difference but a regional network of flying taxis could enable the northern towns to develop a single, integrated economy - at least for a business elite.

But it is the part-time commuting use-case that strikes me as particularly likely to succeed. Let’s imagine I’m a very highly paid banker. Covid has already ensured an acceptance that I don’t have to be in the office every day but I do need to be in several times a week. Currently, that limits my reasonable commuting range. But with a Lilium-style jet, I could live in a picture-postcard village in the Cotswolds (Burford, for example) and commute into town in a matter of minutes. With vertiports at Canary Wharf, the City, Victoria and Kings Cross, the majority of London’s office hotspots would be within walking distance. Obviously, the pricing would be high - but with each vehicle having just five seats, we don’t need that many people to decide that they want to live in the Cotswolds for it to be worth Lilium running a route.

It could be quicker to Canary Wharf from Burford than from my home in Walthamstow…

So, in summary, there’s a lot of money going into flying taxis. They are going to be a lot more price-accessible than a helicopter; their current nearest equivalent. Models vary from operating like true urban taxis, to something that looks more like regional networks. While they are electric, they are going to use a lot of electricity. And no-one wants to talk about birds…